Celia van Wyk

Johannesburg, South Africa

Note: Permission to analyse and share case material for ISST Certification obtained in writing and held by therapist.

Tom (pseydonym) was a 24-year old sales manager with a high school matric certificate, who entered therapy with issues of poor self-esteem and, ” …to figure out who I am.”

At the time of making his first appointment, his girlfriend of five years, had just ended their highly stressful and conflicted relationship. In their association the girlfriend acted as the dominant partner and Tom generally played a submissive role. Her ending the relationship left him shattered and extremely traumatised.

Tom described his father as a soft-spoken man. Tom said he was a passive and noncommunicative parent. Even so, their relationship was and still is fairly good. Tom and his two years’ younger brother also got on well. His interaction with his mother however, was highly conflicted. Both his parents were rather emotionally undemonstrative.

Tom said his paternal grandfather had high expectations of him, demanding that he be “Mr Perfect”’ and “carry the family name with pride.” Yet, in this grandfather’s eyes, Tom did not seem to meet these expectations, and Tom said he “never feels good enough”.

Tom described the domestic atmosphere in his parents’ home as “disconnected”, where “everybody was just doing their own thing.” His parents’ marriage was sound, as was the extended family structure, consisting of aunts, uncles, grandparents, nephews and nieces – all of whom often joined together at special family gatherings. There were more positive emotional connections during these times, but, apart from his mother, Tom did not mention any meaningful relationships with other female family members or friends.

Tom had a history of smoking and using drugs, and when entering therapy he was abusing alcohol quite heavily on social occasions.

Tom described the heart-attack and death of his maternal grandfather when Tom was 13 years old as traumatic. He had a very good and strong relationship with him. Another trauma occurred at age 14. When riding his much-loved bicycle, he was attacked by a man, who forcefully took the bicycle from him. Tom did not receive any trauma counselling for this incident. At the age of 16 he experimented with Satanism and its related spells for a short period, out of “curiosity”.

Tom acknowleged that he was a scared boy, and even now as an adult, said he had little courage, especially with regard to his social life. Although he was of strong body build, he did not like to take any risks – not on his own, nor with friends. Neither did he participate in any daring activities, especially those involving heights and speed. However, as a spectator, he enjoyed social outings to such events.

In therapy, apart from sandplay, Tom and I also did narrative work, as well as personality development techniques and journaling, focusing on left and right brain stimulation activities. However, he loved the sandplay and preferred it to any of the other therapy procedures and modalities.

Tom was in therapy with me for 14 months and had 38 therapy sessions. He came to therapy on average 3 times per month. His sand process consists of 13 trays of which only 1 was done using the dry sand.

When I started working with Tom as his therapist, I could not dream how significantly the process of sandplay would encourage and bring about the healing work that was essential to his wholeness as a man. During our work together we would both be witnesses to the powerful psychic forces and tremendous inner strengths facilitating the psyche’s natural capacity to heal itself. For me, and I know, also for Tom, it was an utterly astounding and so beautiful experience. It is an honour to share his personal growth journey with the reader of this case study.

Tray 1 – Wet sand

The primary symbols in Tom’s first tray are the soldiers, the barricade fences, an empty pond, a tortoise, a crocodile, and a ring of ivy, a fern, two fir bushes, and two helicopters.

The first item Tom put in his tray, was the fern, of which many of its species are heterosporous (having both male and female spores). Perhaps this early gesture in the sandplay carried the potential for his healthy integration of the feminine qualities into his masculine psyche. He added all the greeneries and then the pond, making sure it was well-fitted by pressing some sand up against the sides. His movements were firm, but at the same time gentle. He worked in silence.

The next items were fir bushes and fences at the left and right sides of the tray. This was followed by the crocodile, the tortoise, and the soldiers. Two flag bases, from which the flags were removed, were put at the near left and right sides of the pond. Perhaps he set a foundation for raising the flag of his own identity later in his work. He put the helicopter in the near right corner, and said he was done. But then placed another helicopter in the near left corner, and threw some bushes over the helicopter on the right, as if to camouflage it. His focus shifted again to the left, where he manoeuvred the fir bush around the helicopter in that corner.

At the end of his work, Tom said it was strange. He also mentioned that he initially felt anxious working in the sand, but started relaxing as time passed. He had no associations to share.

The surface of the tray has been divided in nearly equally proportioned sectors, and in two diverse categories. Firstly, the two fenced off, restricted military zones at the left and right sides of the tray, and secondly, the remaining larger region between them. This latter area dominates the scene and immediately draws attention with its lush fauna and flora and the empty dry pond placed on a diagonal slant in the centre.

At the tray’s far left and near centre front are two prehistoric reptiles, a tortoise hiding under the ring of ivy (far side), and a huge snarling crocodile lurking under the front centre palm tree. In the near left corner, surrounded by a large fir bush, an aqua coloured helicopter sits waiting. The flowering plant in the near right of the tray suggests this area may once have been a rare nature reserve or park that should have been cherished and protected. Now, with the lurking reptile and the surrounding military, this is definitely not a safe place.

A heavily barricaded military zone stretches a quarter of the tray’s width from the near left to the far left corner of the tray. On the right side is a second and shorter tightly fenced-in military zone. Its barricades run askew from the far right corner to the centre of the tray towards the dry pond, where it aggressively penetrates into the central terrain, then turns abruptly, its sharp rectangular corner pointing straight at the centre of the pond. From there, a horizontally positioned fence cuts the tray in half. This leaves the remaining lower area open, functioning as an entrance to the “park”. The upper barricaded military terrain remains a caged area.

When sitting with this tray initially, the scene felt as if it carries tense, frightening and vulnerable feelings – even a possibility of being ambushed and a little out of control. There was also a sense of strained contrasts causing a feeling of strong holding between opposites: a dry pond and lush plants; prehistoric and modern objects; camouflaged aircraft in open space, yet the ready one fenced-in and immobile; flag bases without flags; and finally, the green of soft plant life versus dark killing aggression of the military.

These sensations are evoked by the threatening presence and activities of the armed soldiers in the barricaded zones, some of them crossing at the tray’s far periphery; others already deeply infiltrated into the park. Individual soldiers stealthily hide behind the empty flag bases, aiming their guns, ready to shoot. There is also one at the near right entrance. At the same time two helicopters at the near left and right corners of the tray suggest reinforcement, escape, flight – or a victorious exit.

Comprehending the setting in its totality, I realised while looking at the tray – almost with a shock, that this might be a combat zone. Soldiers are aiming directly at the defenceless tortoise, others at the pond, some at each other, or even at anything in between in the park. Its total perimeter seems to already have been invaded and taken hostage, not only by men, but also by their modern defence mechanisms (the two helicopters).

The scene also carried a feeling of anticipation, a readiness, constrained action and courage. All these warlike energies that I sensed while analysing the tray, left me questioning my felt experience of the tray. Through Tom’s therapy process, I came to learn that underneath his calm quiet exterior hid a very angry young man.

Looking at the tray from this perspective, there is much strength in its potent masculinity. A lush fern grows near the left side of the empty pond, the latter having the possibility of being filled; lots of vegetation – an affirmation of life, a flower plant already in bloom – all symbols of renewal and growth. Along with the sense of danger there is also an air of freedom and safety. With ample signs of shelter and protection, the bushes provide a soft sanctuary. Both the helicopters provide means of getting Tom out of dangerous situations. They are camouflaged, suggesting he has planned ahead for an escape if necessary.

One of the most important focus points at the centre of the tray is the destitution of the dry, empty pond, yearning to be filled with life-giving water. Recalling the care Tom took to construct and place the pond, lends the sense of his yearning for the life-giving, nourishing waters of the Self.

In this first tray of Tom there appears to be evidence of issues surrounding the mother and feminine archetypes. This is seen in the diagonal cross points within the pond, and especially its axiomatic connection with the crocodile. The pond, with its uterine form, is empty and dry, which may represent a lack of nurturing experienced from his mother. I remember when Tom added the pond to the tray that I felt a bit emotional looking at it from where I was sitting in the room. Perhaps the barrenness of it reminded me of my own lack of mothering and nurturing as a toddler after my mother died in a motor car accident. When analysing Tom’s process, I recognised the element of counter-transference here.

The huge crocodile may symbolise the devouring aspects of the negative mother. This negative mothering and dangerous feminine quality appears to have been replayed in Tom’s relationship with his controlling lover, who ultimately rejected him. The negative feminine qualities have resulted in Tom’s wounded anima and emasculation.

The large crocodile has a prominent position in the tray. It is out of proportion compared to the other figures in the tray, and in length it exceeds the size of the pond. Tom’s mother’s influence may have determined Tom’s perception of the masculine and feminine roles, as well as of his own masculine identity. This dynamic was recently replayed by the sudden ending of his relationship, which left Tom bereaved of the girlfriend’s person as well as his sense of manhood.

According to Kalff (2003), crocodiles link the conscious and unconscious together, as they are both land and water creatures. She mentions Jung’s idea that, “…such theomorphic symbols always apply to unconscious libido manifestations” (p.77). She then continued with Jung’s explanation that crocodiles as symbols:

…either belong to the unconscious in general or point to suppression of the instincts. The regression caused by repressing the instincts always leads back to the psychic past and consequently to the phase of childhood where the decisive factors appear to be, and sometimes actually are, the parents (1967, p. 180).

The crocodile in Tom’s tray is placed in the tray adjacent to the area of his solar plexus, described by the WordWeb Dictionary as “A large plexus of sympathetic nerves in the abdomen behind the stomach… (as) part of the sympathetic nervous system”, which activates the fight, flight and freeze responses in humans. The constant fighting and stressful relationship with his mother did not fulfil Tom’s essential needs for positive care and nurturing and appear to be related to his emotional emasculation.

The more remote and unreal the personal mother is, the more deeply will the son’s yearning for her clutch at his soul, awakening that primordial and eternal image of the mother for whose sake everything that embraces, protects, nourishes, and helps, assumes maternal form (Jung, 1983, p. 47).

Tom’s need for therapy was stated as “finding myself” and finding relief from the trauma of losing his girlfriend. In this sandplay work Tom confronts his underlying conflicts and losses. In the androgynous symbolism of the firs and their healing powers he reveals his inner resources associated with the birth and rebirth of his masculinity and the discovery of the healthy feminine archetype.

Tom did not accept his aggressive shadow. At times he would be so angry with problems in his life and even with himself, that he could, in his own words, “kill”. During his clinical history, he revealed that he was severely troubled by a self-inflicted cowardliness and inferiority, resulting in his inability to trust, curtailing his own valour by feeling paralyzed about taking risks.

According to Tom, even as a small boy, he could not identify himself with the typical male figure, seriously impacting the development of his masculinity. In his most impressionable years, his passive father was an ineffectual role-model, providing Tom with few, if any, emotional, spiritual or psychological tools for how to achieve a fulfilling life as a man. In addition, in many ways, Tom experienced emasculation. An inattentive farther, the lack of a strong exemplary male figure in his childhood, and his own delicate disposition, robbed Tom of his authentic male identity, forcing him to associate more with his mother’s controlling animus. At age ten, Tom was exposed to the anxiety and trauma of the radical political changes in South Africa when he, as so many Caucasian youths and men of his generation, experienced a loss of self-image and a “cultural emasculation”.

In addition to all of this the most significant negative influence was the constant and relentless downgrading and unattainable expectations of his critical paternal grandfather. As a boy, this had a serious effect on him, creating an inferior feeling and belief of “never being able to do anything right”, resulting in Tom’s subjective sense of having no validity as a human, and later, as a man.

Tom mentioned that since he was very small, he had a recurring dream – whenever someone pressed on his arm or leg it became numb and shot through with pins and needles. He acknowledged that in real life he often does feel “numb”. This spontaneous talking about the recurring dream reminds me of Weinrib’s (2004) observation with one of her clients that the creation of the first picture in the sand, “…provided an initiation into the analytical process” (p.118). This is what I also noted with Tom’s first tray. I felt an openness and certain level of trust from him, as well as willingness and eagerness to work in the sand.

On an unconscious level, the numb feeling in his dream seems to be a way for Tom to dissociate from his anger and “kill” his potential aggression that he could not express if he was to remain a good boy who carries the family name in pride.

The empty pond in his tray mirrors his dry, mechanical-soldiery way of living and reflects an unstable and ineffective way of walking through the world. The consequence of such an imbalance may lead to increased anxiety about not being good enough and periodic acting out of his aggression.

This empty pond also carries the grief of his many losses, inferiorities, shame, fears and sorrows and is, perhaps, waiting to hold his tears.

Tray 2 – Wet sand 3 Weeks later

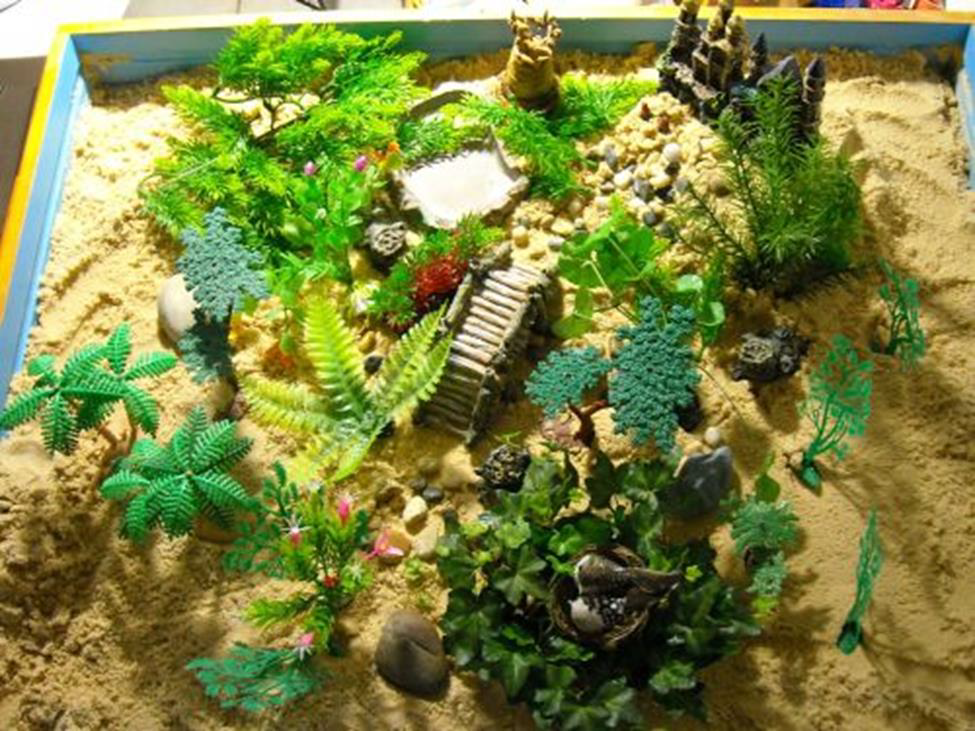

Tom’s process deepens here. Tray 2 is a circle, wonderful embroidery of green growth and life. Apart from the noteworthy nesting birds centre front, there is no human or other animal activity; however their presence is suggested by the castles and a bridge. The highly energetic and circling motion of the dense plants indicates a powerful development of psychic energy.

The two castles were the first symbols Tom placed near the tray’s far right corner. He put them on a small hill to raise them higher. The greenery and a flowering bush were added in a circular pattern. He placed the bridge at the centre of the tray, followed by the pond at the far centre of the tray. He added three tree stumps, and a baobab tree between the castles and the pond. He then scattered little pebbles in front of the castles and added the big rocks. Lastly he put the nest with birds in the centre of the ivy ring.

Tom said it was gratifying working with the bushes, and he called this scenario a “forest theme”.

Here Tom’s psyche moves to a more nurturing environment, exposing more of his vulnerability. The trees are closer to the pond, which is now accessible by way of the bridge. The tray seems stronger and better organised. The masculine feeling from tray 1 is also present here. The overt aggression and defensive qualities of the soldiers now become castles that house and protect their inhabitants. The feminine component now appears as flowers and a mother bird with her chick in the nest. The empty pond and the fern are now placed near the castles. The castles also represent home and the Self and these are here and in a royal way.

According to Bradway & McCoard (2005) the castle is an androgynous symbol: “As a place to live in, it is a feminine image; as a fortress, it is a masculine image” (p. 169). They also refer to “bridging the opposites” (p. 86). This component is further emphasised by a real bridge in Tom’s tray. Castles are also symbolic of the unconscious’ protection of its unexplored secrets.

Tom has provided the castles a panoramic view over the scenario, directly facing everything in the tray, from the circle of ivy and its nesting birds, the soft pink flowers in their delicately leafed shrub up to the baobab tree and the pond, and the large fern growing at the escalating bridge’s footing. Both the baobab and castles bear a resilient energy of solidity and endurance.

Where Tom’s first tray exudes an aggressive menacing energy, this second tray is vibrant. The negatively aggressive chauvinism begins to shift, and the feminine energies are in harmony with the masculine energies. Large trees now grow close to the desolate pond, some of their branches stretching across it, providing shade and protection, shielding it against its own dry emptiness and creating a feeling of empathy and compassion.

The ring of ivy is now placed where the crocodile was in Tray 1. It surrounds the nesting birds, like a protective crib. Symbolically the ivy ring with something nesting in it, something embryonic, relates to new life. As Tom said; the birds were added “…to bring in some life, because there are so many bushes with no birds”.

Another important symbol in this tray is the baobab. This is a huge South African tree, having the capacity in its wide gnarled roots, branches and capacious trunk, to hold life-giving water. They often live for hundreds of years. The baobab is a strong tree, highly resilient and powerful. Although the tree has feminine symbolism, portrayed in its crown of branches and its roots, strongly anchored in the earth, its solid vertical trunk carries masculine energy. In this way, the baobab is a union of the opposites. Interestingly is that the baobab was placed nearest to where I was sitting as therapist. With its placement, I experienced a strong feeling of positive transference from Tom. Did I portray the powerful, safe and nurturing feminine qualities he needed to discover and nurture to awaken a healthy anima function?

Tom placed three tree stumps around the bridge: one just below the pond to the left; one at the right foot-side of the bridge; and the third, higher up on the periphery of the trees on the trays’ centre right. The triangle formed by these three stumps which expose the cut-off remnants of highly masculine tree trunks, seems very important. It symbolises the incapacitation of Tom, as well as his “stumped” background and psyche. Centred within this symbolic configuration, is the bridge, here an open passage towards an elevated place, a castle with a baobab tree. By crossing through the triangle formed by the stumps, the bridge provides a pathway of hope and freedom. This bears a striving to attain wholeness via the aspects of a trinity, of which the number 3 is a strong archetypal masculine symbol.

In her book, Singer (1994) noted that trees and their upward growth are symbolic of the three worlds, hell, earth and heaven. This is reflected in a tree’s threefold structural makeup of roots, trunk and foliage. It also denotes a microcosmic life as consistency, proliferation, growth, and the generative and regenerative processes (pp. 76-77).

Tray 3 – Wet sand 1 Week later

Before starting his sandplay process, Tom mentioned that he felt emotionally unbalanced, especially at his workplace. Perhaps the psychic movement experienced in his first two trays contributed to these feelings of imbalance foretelling the need for sacrifice of inner beliefs and behaviours not to his benefit anymore. At the end of the session, after working in the sand, he said he felt more relaxed.

Tom commenced his work on Tray 3 as if uncertain, by first touching the sand lightly and then using flowing movements from side to side with his hands. From its beginning, Tom’s approach to Tray 3 differed from that of his previous trays, indicating that a transformation had already started. I experienced Tom’s presence as more composed, more thoughtful and not evidencing his working randomly all over the tray as he had done previously.

The first item he positioned in the tray, was the centre starfish, followed by the second one on the far left, the huge scallop shell in the near right corner, and the smaller shells, sea creatures and the sea plants. This was followed by the mountain in front of the scallop shell, the pink squid, the blue shark and a brown dolphin. Next he placed a seahorse with a nearby boat and the three large rocks in the far left corner. Lastly, he added the animation character SpongeBob SquarePants wearing his beach hat on his head.

The tray indicates the bottom of the sea, where lives SpongeBob SquarePants, an animated sea sponge, whose outstanding “sin” is “ …excessive love of others, shown in his over-eagerness to do good and help” (SpongeTronXYZ, 2007, para. 7). In some ways this symbol resonates with Tom’s habit of accepting everyone, friends or family, without questioning their motives or actions. He described himself as a well-loved friend, but at the same time resented his own SpongeBob servility.

The movement in this tray signifies a shift toward a deeper layer of the unconscious into new territory. As such a decent can be frightening, Tom also reveals the resources that support him on this level.

The two five-armed starfish in Tom’s tray carry significant symbolism, in their capacity to regenerate when wounded. They also carry symbolism of the number five, as the wholeness of the complete human being with two arms, two legs and a head. As such, starfish carry healing and renewal, as well as the potential for wholeness. Jung (1959/2008) refers to the archetypal qualities of the number five as, “the number assigned to the natura, thus the material and bodily man in so far as he consists of a trunk with five appendages” (p. 373). Archetypally Tom’s geometric proclivity would here include the five pointed pentagram, which geometrically is the last solid form to be made from other geometric shapes fitting together perfectly.

Another prominent symbol in this tray, is the huge scallop shell, also known as a pilgrim’s shell. The imagery is linked to its shell’s out-fanning grooves. In lieu of several routes on a pilgrim’s journey, these come together in one single point (Website Caminoteca, section Pilgrim’s Shell, para. 6). This is Tom’s journey, his quest of “coming together” to find his own vital life-force.

The seahorse is unique in that it is the males that carry their unborn offspring. The males give birth to the babies. In this seahorse, Tom discovers his own inner archetypal fathering and nurturing. The seahorse is not alone; it hovers nearby a large boat. Perhaps this is the means to take Tom where his psyche calls him.

With the sea-turtle imagery, Tom will be able to migrate to far away and unknown places within his unconscious. It is here he will be reborn in his return to the original Self.

For Tom, these aspects may be portrayed by the natura, as Jung called it, used in this tray. Here Tom has descended down to a “sea bed”, where he discovers the archetypal elements that will guide his way to his individuated Self. In truth, this tray can be seen as the beginning of a unique journey that Tom is now ready to undertake. Kalff (2003) said: “ …every human being must find the way to himself. This path leads to the experience of the divine” (p. 133).

Perhaps the intrinsic meaning of the tray is far beyond what Tom was consciously seeking when he entered therapy. At the time he felt “…emotionally out of balance” and had exhausted his own abilities to rectify things. The barrier between his consciousness and the unconscious gives way and he sits quietly at the bottom of the sea. It is the mother of all life. This is the source of the spiritual mystery and infinity, of death and rebirth, timelessness and eternity. Here the pilgrim comes to rest to gather energies for the transformative work ahead.

Tray 4 – Wet sand 1 Week later

Tom started the session by saying he felt exhausted, but would like to work in the sand. He also said he felt more confident in himself, especially at work. He looked at the shelves and said, “Tonight I have no idea what I would like to do”. He then started using the flat of his hand, sweeping the sand lightly from side to side in horizontal and vertical gestures.

He first placed the four delta-wing airplanes in the tray. This was followed by a tow-truck and four helicopters. Using his forefinger to draw lines in the sand, he made divisions between the parked vehicles. He then added two silver cars and the large black box. This was followed by the coloured sticks and fences, and lastly, the road signs.

In his previous tray, Tom prepared for a critical life journey with the energies of the boat, the seahorse and the sea-turtle. In this tray there are three diverse modes of transportation: three ground vehicles; four jets; and four helicopters. The two cars and a tow-truck stand askew in a triangle, as if carelessly parked, while the helicopters are neatly arranged in a line. The delta-winged fighter planes are carefully arranged two by two facing each other. They wait silently as if put on hold. This lack of animation lends this tray an uncomfortable suspense. Further exploration revealed that there is only an entrance.

Despite a prominent sign, there is no exit. Everything in this scene is fenced in; doubly barricaded by the additional walls of the tray. As in Tray 3, Tom has obstructed any way out of this site.

The straight lines and enclosed spaces greatly restrict any movement of energy. Most of the tray is additionally framed with the white fencing. The double boundary of fences might embody defensiveness or fear. Although there are open gate spaces, they are flushed against the boundary of the tray. On the other hand this may represent safety measures taken to guard against intruders into this psychic space where Tom nurtures a newly developing masculinity.

The black box in the near left of the tray is disproportionately large. It carries a sense of standing apart. When Tom found the box, he took off its lid and put it aside. He then purposefully placed the box upside down and diagonally in the tray. Its symbolic meaning is therefore complicated; the more one regards the scene in its totality, the more the box’ pitch dark colour, overbearing size and sealed density, render it somewhat ominous and menacing. It may be a black place for Tom to take shelter or hide in, or to even give up and withdraw from life. It is something unknown, dark and foreboding, a prowling shadow in the night. I felt very cautious about this. While holding the possibility that the box may contain new, as yet, unknown qualities emerging from the unconscious, I maintained vigilance about the possibility of self-destruction or suicide.

Jung cautioned about the unpredictable nature of the individuation processes. Todd (2007) summarised it as a journey of unexpected twists and turns and commenting that the deeper the process is, the deeper the subjective experience of discomfort and uneasiness (p. 13).

Albeit, when looking at the tray, and ignoring the box, there is a feeling of ascension, of “being prepared”. It appears that the pilgrim from the previous tray has set upon his journey. Even a tow-truck is present in the event of an emergency. In this fourth tray there is no organic life present, and no movement. Yet, the whole scene exudes a tangible vibration and atmosphere of intense suspense – everything seems to be dormant – but waiting. In fact, when the black box is taken into account, there is the added element of angst – as if the whole scene is suspended – frozen, and despite the parked cars, all life has suddenly disappeared.

Tom used to be terrified of flying. This was overcome when he and his lady friend, as young students, travelled to the United Kingdom to work for a year. He said this tray reminded him of how scared he was on that trip, that first time he reached beyond his limitations and took a risk to make life different. Perhaps here in Tray 4, Tom reflects back on that dark time acknowledging the pain of his selfimposed limitations, while recognizing the freedom he found by asserting himself and taking a chance to make life different.

Tray 5 – Wet sand 1 Week later

Tom started his work in Tray 5 ruffling the sand, saying, “I have a feeling on my stomach. I think I’m tuning in. Tonight I am going to just put in the sand what my eye catches”.

Singer (1994) described Jung’s feeling function as a judging process that “… depends upon a personal or subjective value system – there is something conscious or unconscious, against which objective reality is measured”. She continues by stating, “Feeling operates with spontaneity, responding directly to a situation before analyzing its many aspects to determine its worth or usefulness. It says, I like that, or, that will never do. Feeling is associated with empathy” (p. 331).

One cannot help but think about the huge crocodile at Tom’s solar plexus area in his first tray. In his second tray it was replaced with a nest with birds, indicating a shift from the untrustworthy negative mother energy to a more nurturing motherly environment, and in Tray 5 the region of the solar plexus is neutralized, looking controlled and balanced. This projects a calm flowing energy along with feelings of fearlessness and relaxation.

Tom first placed a prominent square water feature in the centre, followed by bridges, the mountain and the Eiffel tower. Recalling the dry pond in Tray 1, water is now indicated in abundance by the presence of a fountain and three large urns. Here it is readily accessible via the bridges, which connect the water feature to the rest of the tray. I recall my thoughts when watching Tom put the water feature in the tray: “Is the Self being watered here in order for it to emerge?” Pondering this idea I recall that I could hardly breathe. The room felt intensely heavy, as if the entire configuration of his ego structure was shifting. This was a remarkable and humbling moment of transformation to witness. I was rivited to my chair and felt such remarkable closeness to Tom. Curiously, I doubt if Tom was aware of this powerful moment at all.

Tom arranged the tray in four equal rectangles defined by the casually strewn white pebbles. These form two lanes through which the vehicles now comfortably flow. The previous tray’s black box was now replaced by a much smaller and light-coloured one at the far right corner of the tray. Now it is a landing pad for the blue helicopter. Unlike the former grounded and camouflaged helicopters, this one is fully functional. It provides access to the newly developing psychic qualities that are present here, as well as an overview. Next to the near bridge is the Eiffel tower, a graceful and well-balanced metal structure. Next to the far bridge stands a solid mountain. Both the Eiffel tower and the mountain carry new qualities of a strong and balanced masculinity. Clearly the newly developing masculinity from the previous tray continues to evolve.

Now Tom has a fluidity of movement on both the vertical and horizontal axes, also indicating movement toward a more balanced personality. The upwardly-angled bridges and the elevated helicopter make a connection between what is higher, the heavens, or masculine elements, with the grounded horizontal movement of the vehicles on the earth, or feminine qualities.

Although this tray may not be a true mandala, the rounded edges of its four rectangles and the pebbles at the base of the fountain, suggest circles, which encompass the square center. Archetypally, the combination of the square and the circle also carry the union of the masculine and the feminine. The repetition of this indication of a union of the masculine and the feminine suggests a precursor to their complete union in the Self. Editor Beebe stated in Jung’s book on the masculine (2003):

Jung’s notion of the stages of life implies a lifelong series of initiations. The developing individual struggles successively with problems typical of each time of life, and these problems are never fully solved. Rather, they serve the purpose of promoting consciousness (p. 26).

Schopenhauar’s “principium individuatios“, and Nietzsche’s “life-task”, which Jung called “the psychological drive to be the Self that truly is… becomes the moral imperative to accomplish one’s mission of individuation” (p. 26). And “It is only the adult human being who can have doubts about himself and be at variance with himself” (p. 27).

Intrapsychically Tom shows through the use of these symbols his willingness to get grounded and connect to the Self, to no longer be inflated but rather embody the Self in his daily circumstances and life. Here Tom’s symbolic construction effects a connection to the Self and a concommitant grounding in the material world. No longer will he suffer the pains of his compensatory inflation. Rather he will embody the centeredness of the Self and the ego’s service to its centrality in his daily circumstances.

In the prior trays, Tom grapples directly with the obstacles he faces. Here he begins to find some resolution. The energy during Tom’s therapy session felt light, bubbly and happy. He mentioned when he finished the work that his tray seems more “friendly”, and he especially liked the center-part.

And yes, it was such an “optimistic” tray, for me. I recall feeling that I was honoured to witness this profound transformative work that was taking place and that there was, most certainly, hope for further development ahead.

Tray 6 – Wet sand 1 Week later

The sandplay session started with Tom ruffling the sand slightly. His movements became stronger as he began to relocate some of the sand away from the sides and move it to the centre of the tray. He then started to divide the mound in the middle into four hills – two at a time – exposing the tray’s blue bottom. The first division became a roundish island at the centre left side, and the rest, a high peninsula in the far right area. This is connected to the island by a bridge. The other mounds were similarly divided. Tom patted the large centre right hill into a firm and neat dune, and also linked it to the smaller egg shaped islet with another bridge. The latter were then made reachable from the surrounding beach by a small bridge.

With the divisions of the sand, Tom began the process of differentiating the various aspects of psychic material that had heretofore been unclear, resulting in his sometimes confused or contradictory behaviour and attitudes. Here we think about his constant bickering with his mother, the submissive role taken in his lost relationship and his need, but also fear of, intimacy as a man seeking authenticity.

He added trees followed by the Chinese fisherman, a mountain in the near left corner, large rocks and small pebbles, a row boat as well as a sailing boat, a bicycle, a tree stump, the umbrella tree in the far left corner, fir bushes, a crab, a lizard, and the two Dalmatian puppies. He then placed a snake in the umbrella tree in the far left corner.

The varied dimensions of his landscape in the sand reflect his newly developing capacity to view and act on his inner and outer world experiences with dispassionate reflection and critical thinking.

Tom said he was done, but hesitated and added the cartoon characters, Obelix, a constant companion of the animation character Asterix, on the left island next to a rivulet, and Patrick Star, SpongeBob Squarepants’ best friend, standing on the near right bridge, overlooking the scene. This was followed by the six boys, or men, playing a ball game and a seemingly shy girl, hiding behind a tree near the bottom of the bridge. Lastly, he placed a princess on the bridge, looking towards the island where Obelix is.

The addition of these two animation characters, intrapsychically, points towards the befriending of Tom’s own instincts. He now becomes his own best friend.

Tom reflected on the tray and then said that the sand areas stand out, and that it is really beautiful. He called his tray “A fun day out”.

The dynamic in this tray differs profoundly from the previous ones, in that Tom not only opened up vast areas of depression reaching the blue bottom of the tray, but created several mounds, and flattened the area on the far right side of the tray. Opening up of the blue bottom here clearly indicates the presence of water but one also gets the feeling of plunge into a dark unknown place in his psyche where dormant energies lie ready to be awakened. The unconscious energies activated by this descent may effect powerful feminine psychic movement in support of the development of Tom’s anima, beautifully represented by the princess on the bridge.

When looking at the dunes formed by Tom we refer to Turner’s (2005) explanation:

The appearance of the rounded hill or mound in sandplay may well function in a way that is similar to the ritual centering place of the Buddhist stupa. In one sense, every mountain fashioned in sandplay is made by hand and carries the sacred connotations of a stupa (p. 221). And,

…when the form is born directly from the sand as the ground of being, the immediacy between client, psyche and symbolic form is so great as to be inseparable. There is an intensified investment in the particular symbol that is created entirely by hand (p. 230).

Turner’s description reminded me of the ritual and sacred feeling present when Tom sculpted the sand. I could not help but be impacted by the intense psychic energy in the tray. Looking more closely at this energy we see that a strong connection is formed between the earth (sand, body, conscious) the depths (water, unconscious) and the heavens (mounds), forming a horizontal and vertical axis where all the energies culminate in the centre with the princess. This is the symbolic strengthening of the ego-Self axis. This opens up the possibility for Tom to move deeper into the unconscious where he will access more psychic qualities that are properly aligned to the Self.

Furthermore the construction of the tray and the placement of the different figures support Tom’s readiness to work on this level. The movement in his tray feels circular, channelling these energies towards integration and the constellation of the Self.

The fact that Tom flattened the sand on the far right side may indicate a compensatory and defensive act to retain more control following this powerfully transformative symbolic work.

The tray feels happy and light. Here Tom strikes a balance of the elements water, wind, earth, wood and metal. The tray radiates a vibrant energy with clearly defined motion paths in the water and on the land. Everything is accessible; however the fire element is not yet present. We will look for its appearance in Tom’s work ahead.

Apart from the soldiers in his first tray and the animation character of SpongeBob in his fourth tray, this was the first time Tom again used people and domestic pets (the dogs). Now the angling fisherman appears, and as we will see, from now on regularly in Tom’s future trays. Weinrib (2004) refers to this phenomenon as that the client sometimes during his process uses a single figure of the same gender to identify with consciously, and as the process progresses, the relation and energies of the scenes in the tray and with the figure become more substantial, and thus form part of the emergence and activation of the re-born ego (p. 86).

In eastern cultures, the Chinese fisherman is a powerful symbol, representing the ability to reach into the depths of the unconscious. This capacity affords him a rich relationship with the subliminal. In this way, the fisherman is a guide to inner knowledge. The fisherman and his rod form a connection between the conscious and unconscious (Kalff, 2003, p. 62). The use of the fisherman in the tray also appears to be an indication of Tom’s willingness to work on deeper levels.

Jung described fish as symbols of unconscious’ content, emotions, or life energy, stirring in the unconscious from the beginning of our life. As such, fish can also symbolize the Self, or the inner Christ, and the act of fishing represents the active search for material from the unconscious.

Steinhardt (2013) talked about fishing as the symbolic act of bringing contents from deep within the unconscious to the light. Estés (1994) explained that the nourishment gained from the unconscious waters by the fisherman is filled with “the entire elemental feminine nature”, which includes the cycle of life-death and life-nature, as death is always part of life’s new beginnings (p. 139).

This fisherman is not alone. Although he sits apart, he is accompanied by and linked to the small circle of boys playing on his far piece of land.

The serpent in the tree appears to be moving upward, recalling the rising spiritual energy of the kundalini. In the Hindu and Buddhist cultures this represents the awakening of dormant spirituality and a movement toward enlightenment (Fontana, 2010, p. 100).

From a more Western viewpoint, Jung viewed the serpent in the tree differently. Jung referred to it as a “…arbor philiosophica, which derives from the paradisiacal tree of knowledge …a daemonic serpent, an evil spirit (that) prods and persuades to knowledge… (it has) a great many connections with the dark side”. Jung connected this to the archetypal shadow in all of us: “We have no choice but to accept this shocking paradox after all we have learnt about the ambivalence of the spirit archetype” (Jung, 2003, p. 182). Although these two interpretations of the serpent in the tree appear antithetical, both the Western and the Eastern understandings concern a deepening of knowledge through a radical transformation of personal identity. To undergo this development necessitates that the current position of the ego be surrendered. This is a daunting and, often, terrifying undergoing.

Perhaps to help with this transformation, the bicycle at the far centre demands capacity for balance and trust not to fall. The appearance of the bicycle is reminiscent of the traumatic childhood incident when Tom was 14 years old. Knocked off of his bicycle by a thief and unable to defend himself or his property, his bicycle was forcefully taken from him, leaving him traumatically emasculated. In this tray the bicycle returns in a positive way, supporting his psyche’s development. “The bicycle symbolically evokes a vehicle of psychic energy and progression that is personal and collective, and under the command of the individual ego” (ARAS, 2010, p. 440).

Tom placed the princess in the centre of the tray where the empty dry pond once was. Here she is on a high bridge that connects the island to a much vaster domain. The fact that she stands exactly where the dry empty pond previously was is not incidental. Standing on the highest point in the centre of both the bridge and the tray, she is the heart of the scene. Significantly, the princess is the healthy anima. She carries the internal feminine qualities that Tom will need to guide him on this journey to the central archetype of the Self. Jung speaks about the gravity of this undergoing:

Contrary to all progress and belief in a future that will deliver us from the sorrowful present, they (the) collective contents that stand in… compensatory relation to our highest rational convictions and values), point back to something primeval… They show us, as the redemptive goal of our active, desirous life, a symbol of the inorganic – the stone – something that does not live but merely exists or ‘becomes’, the passive subject of a limitless and unfathomable play of opposites, ‘Soul’, that bodiless abstraction of the rational intellect and (the) ‘spirit’ metaphor… The hope for a psychology without the soul is brought to nothing, and the illusion that the unconscious has only just been discovered vanishes… it has been known for close to two thousand years… Something of the projection–carrier always clings to the projection, and even if we succeed to some degree in integrating into our consciousness the part we recognize as psychic, we shall integrate along with it something of the cosmos… since the cosmos is infinitely greater than we are” (Jung, 2003, pp. 179-180).

Here in Tray 6, Tom experiences the archetypal and personal elements that will give birth to his essence in the Self – the deep unconscious imageries and whisperings of a very intricate soul.

Tray 7 – Wet sand 1 Week later

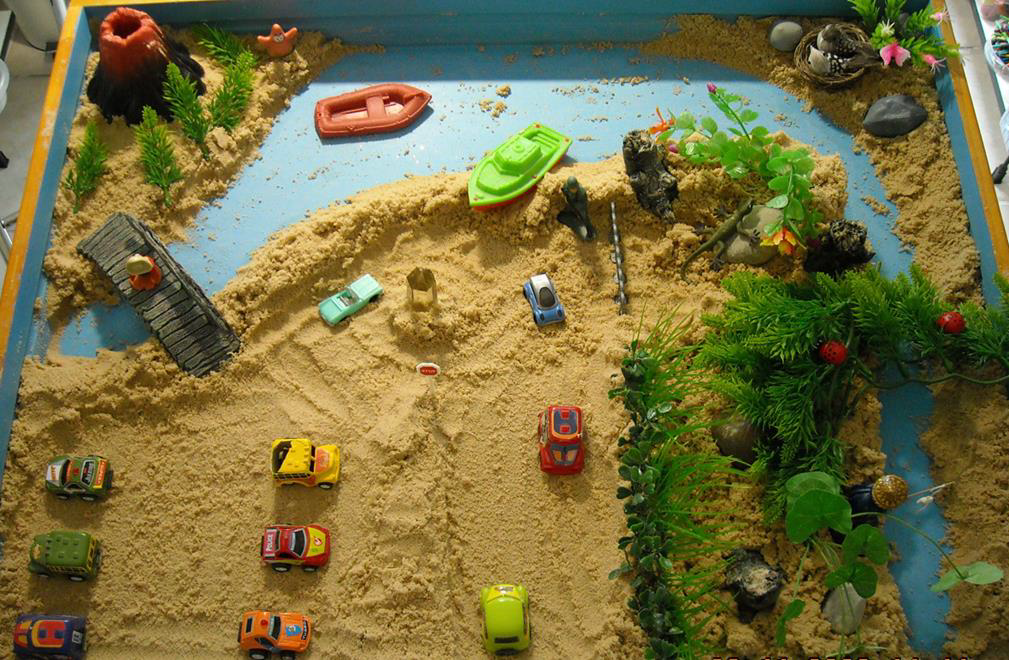

As with previous sessions, Tom started his sand play by sweeping the sand lightly from side to side. He drew an elongated diagonal line in the far left corner and then opened up the sand towards the right, exposing the bottom of the tray to create a lake. He then placed the volcano on the isosceles triangle of sand in the corner. In order to link the volcano area with the flat sand bed in the rest of the tray, Tom added a bridge at the outlet of the lake.

On the right Tom opened a downward strip, creating a vertical river flowing into the lake. On the left of the large open terrain Tom made a parking area with two well-ordered rows of three cars and an opening for vehicular access to the lake. He added firs around the volcano, and then sculpted the sand, moulding a small knoll on the right side of the inlet to the lake, and heightened the banks around the water’s edge.

On the left bank of the river, Tom created a beautiful forest. Here he placed the fisherman angling in the river. He added tree stumps and two red beetles amidst the greenery. The rest of the figures followed: road signs, fences, a cabin-cruiser; and two boats. Tom positioned a soldier, perhaps as a guard, to the right of the cabin cruiser and a large lizard basking on the big stone. On the far right bank of the river Tom placed a nest with two birds and two rocks, one round and the other triangular.

Tom then added two animated characters – Yosemite Sam on the bridge and Patrick (from SpongeBob), on the sand triangle at the far left corner. Lastly he placed the crystal obelisk in the centre of the tray.

The fire element that was missing from Tray 6 now appears as the volcano, the first symbol Tom placed in his tray. Kalff (2003) refers to the volcano as an alchemical process. “In alchemy, transformation takes place in the hot fire. Fire often depicts a renewed vitality, as well” (p. 135). The rising energy of the kundalini in the previous tray has here been intensified with the rising of the molten lava.

According to Weinrib (2004) fire now connects the elements fire, water, air, indicating a more balanced, wholeness of body, mind and spirit, as he continues on his path of individuation. (p. 190)

Tom said that the volcano is a “sight-seeing thing”, a tourist attraction. He said the obelisk was also a “sight-seeing thing”. I recall my own sense of resolve with Tom’s confident and firm placement of the obelisk in the tray. Clearly, this was the confirmation of a strong masculine presence. I held my breath and felt a strong tingling sensation on my stomach. Was this a reflection on my own evolving animus or my shared celebration of Toms’s own establishment of himself as a man?

I came to see that the placement of the obelisk in Tom’s tray was a confirmation, a substantiation and validation of his emerging masculinity. The Encyclopaedia Britannica describes the obelisk as follows:

Obelisk, tapered monolithic pillar, originally erected in pairs at the entrances of ancient Egyptian temples. The Egyptian obelisk was carved from a single piece of stone, usually red granite from the quarries at Aswān. It was designed to be wider at its square or rectangular base than at its pyramidal top, which was often covered with an alloy of gold and silver called electrum. All four sides of the obelisk’s shaft are embellished with hieroglyphs that characteristically include religious dedications, usually to the sun god, and commemorations of the rulers (par. 1).

Another reference (TourEgypt, 1996-2013) describes the obelisk as: “A monolithic tapered shaft that symbolizes the primordial mound upon which the rays of the sun shone first. The tip was usually gilded and often stood in pairs before tombs and temples” (section: Obelisk).

This phallic symbol not only reflects on Tom’s masculinity, but the male power of the sun, and the energy element fire, both formidable masculine symbols. Furthermore it represents masculinity embedded in his own spirituality.

At the end of the session Tom proclaimed that the soldier in his tray is there to prevent people from going into the forest, as only the fisherman is allowed to be there. Tom’s seclusion of the fisherman here and his identification with this archetype may indicate a respite, which may be a temporary defence to provide him time to gather the energy necessary to dis-identify with being a victim and to eventually move into an authentic sense of Self-empowerment.

It is the second time the fisherman appears in Tom’s sand work. However the fisherman in this tray appears to be separated from the rest of it, even though he is a significant part of its scene, he requires protection in his forest abode. Perhaps here Tom tests the depths, as the fisherman continues to fish for unconscious content, which will later be integrated into consciousness. Kalff (Turner, 2013) described the fisherman with his line in the water as follows: “This is the masculine that begins to fish out of the unconscious, instead of moving up to his head. It is very interesting that the masculine begins to change and to reach into the depths…” (p. 274).

It is a very masculine tray, exuding a robust virile energy. This is indicated by the row boat, which moves through manual use of the oars; the red hot volcano; the substantial body of sand that penetrates the feminine waters of the lake; and the cars’ movement along a clear, broad pathway that travels around the phallic obelisk. In addition, the sharp bow of the beached cabin cruiser points directly to this central phallus. Tom begins to take ownership of his masculinity and his sexuality.

However, there also seems to be a moral or threatening implication in the appearance of the crystal phallus. Tom placed a small stop sign directly in front of the obelisk. Perhaps the emergence of this powerful energy requires caution. Perhaps the warning sign carries the vestiges of his conflict about his strength as a man and the inescapable influence of his animus-possessed mother. The question remains if Tom can fully be a man and confront his internalized emasculating mother. To own and fully embody his own masculinity necessitates that he confront these inner qualities of his mother’s power over him. He must acknowledge those aspects of himself that have conceded this important part of himself to her forces. The warning sign is warranted. It is not a task to be entered into cavalierly.

He makes some movement in this direction with Patrick and Yosemite Sam. Patrick Star, whose character is portrayed as lazy and unwilling to act, has been moved from his previously prominent position in the centre, to the far reaches of the tray next to the lava-filled volcano. And Yosemite Sam, a little old prospector, driven to distraction by a mocking rabbit, now courageously crosses the bridge towards the dangerous volcano. Perhaps these weaker qualities that have tormented Tom now move toward the volcanic source of great power from the unconscious.

In this session Tom told me about an incident when he was a small boy. A teacher at school made fun of him in front of the class when he slipped and fell into a pool of “dog-vomit”. This was not the only time she picked on him. The suppressed anger Tom felt as a boy toward that deprecating teacher, now resonates with the wrath of Yosemite Sam, who is determined to shoot that bullying rabbit.

Tray 8 – Wet sand 1 Week later

As was his custom, Tom started the session by ruffling the sand, but this time, he took more time to do so than previously. After pushing the sand toward the sides of the tray into a rectangle, he made a hole in the middle of the sand, opening to the blue bottom of the tray. He then began dividing the sand, forming eight channels radiating from the centre. He then drew a semi-circular channel to encompass half of the eight inner triangles. He repeated this gesture with the remaining four triangles, and then connected the two semi-circles together creating a complete circle.

The number eight is significant in Tom’s work, as it can be thought of as the doubling of number four, four being the number of manifestation – that which has come into form. With the eight triangular shapes, something new now becomes manifest and it is held by the wholeness of the circle framed by the squared edges of the tray. It is a sand spoke-wheel that slowly turns around its central axis forming a beautiful mandala.

Tom chose only one figurine, the fisherman, and placed it in the centre point where he first penetrated the sand. He said, “This is an everyday cycle. I am the fisherman in the centre. My routine is the same every day, and it forms a part of a bigger cycle”. I was deeply moved by the reverence and serenity with which Tom spoke. It felt as if an air of quietude filled the room.

Tom surprised me by saying that he did not have a good feeling about the tray. He said he was not happy. He was upset and angry. There were so many other things he could have done, but he does not have the time for it. He has no other time, except to work. He said “I think I am suffering from burnout”.

While I held his subjective sense of exhaustion, I wondered if the experience of this centering in the Self had not challenged his conscious attitude of being tired of the disempowered way he had been living. I thought of Neumann’s (1999) observation that every psychic gain goes hand-in-hand with the grief of that which is replaced by the new, more evolved qualities. This tray felt mystical and transcendent. The eight triangles enhance this transcendence with the fisherman sitting precisely at the point where all axes cross in its centre.

The sacred aspects of the fisherman are amply described in literature. De Troyes described the angler as, “The rich fisherman” (p. 19), because he had succeeded in catching a fish with which he had satisfied the hunger of all round him…; Perceval meets the king of the Grail as a “fisherman”; and the Biblical reference to the followers of Christ are as fishermen: “…Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men… ” (King James Bible, Matthew 4:19).

Chalquist (2007) called the mandala a “magic circle” and described it as follows:

…A symbol of the Self ‘seen in cross-section’, of wholeness, of psychological totality, balance, and of centering… ; having a clear periphery and a centre and is often built on the quaternary archetype. A protective circle (temenos). Circles, squares, and multiples of the number four or eight represent this wholeness (section Mandala).

The symbolism of eight triangles in a mandala is explained as follows on the internet blog (Heroes 2011 Edublogs, 2010, June):

…stability, harmony and rebirth associated with the resurrection; it resembles the sign for infinity and indicates the limitless spiralling movement of the cosmos; the inexorable turning of the wheel of life; it is a symbol of wholeness as it is two fours, the preeminent symbol of Self.

Singer (1994), on the symbolisms of the circle and the mandala, wrote:

Of all the symbolic expressions of the Self, the circle or sphere seems best to give shape to the ideas of the Self’s centrality, its extensity and its encompassing character… it is the journey of the sun hero crossing the sky in an arc from east to west by day and, from dusk’s descent, returning under the night sea to dawn’s arising. As such the circular path is the analogue for the way of individuation… Mandala is the Sanskrit word for circle; it means more especially a “magic circle” (p. 240).

Allowing the unconscious to guide his hand, this is precisely what Tom did when he created the circle in his tray – first tracking the pathway of one semicircle, followed by the other. We are reminded of Jung’s famous quotation: “Often the hands know how to solve a riddle with which the intellect has wrestled in vain”.

Jung (1978) described the mandala:

The mandala is a very important archetype. It is the archetype of inner order, and it is always used in this sense, either to make an arrangement of the many, many aspects of the universe, a world scheme, or to make a scheme of our psyche. It expresses the fact that there is a center and a periphery, and it tries to embrace the whole. It is the symbol of wholeness… (pp. 327-328). I am now whole in my ego, my ego is a fragment of my personality. The center of a mandala is not the ego; it is the whole personality, the center of the whole personality… the wholeness I call the Self (p. 328).

When Tom finished his tray he was not satisfied with what he had produced. But a few moments later, after he had contemplated the scenario for a while, he changed his mind, voicing a newly-found union with himself and the palpable spirit of the tray, saying, ”I feel more connected with my feelings – I am the fisherman in the centre!” Again the transformation experienced by Tom here seems quite dramatic.

Tom’s centering of the Self is the “wheel of life” with the fisherman at the hub. The connection is real, in balance and on a deeply transcendent level. Tom now truly is the fisherman, and he knows it.

Utterly beautiful.

Tray 9 – Dry sand 3 Weeks later

The week following the work in Tray 8 Tom asked not to do sand work. I assumed his psyche needed time to integrate the deep and intense work done during that session. Therefore we talked about events and experiences in his life. It was evident that he wanted to keep it light providing some general feedback on his day to day life. I respected his request and his psyche’s need for adequate time to process and integrate the symbolic work he has done in his trays.

With the next appointment Tom began by saying he has started to make more time to visit with a lady friend, “… just to talk”.

As this was the first time he worked in dry sand, Tom said he could feel the difference, and that he preferred the wet sand. He initially selected the empty pond from Tray 1, but immediately returned it to the shelf. He then opened the sand in the far right, creating a pond. It quickly became a typical African watering hole when he put the elephant family at its front, placing the calf in-between the two adults. Next he positioned a hippopotamus and her calf on the opposite side.

Next Tom placed the baobab tree from Tray 2 in the centre of the tray and arranged the rest of the scene around it. Behind a diagonal row of four large oak trees in the far left stand a zebra and her two foals. At the left centre Tom arranged some trees and a leopard family. The adults rest in the shade while their two cubs play nearer to the drinking hole.

In the near right corner, Tom connected three large rocks, and settled a gorilla on top of the largest rock in the middle. He placed a mountain behind the rocks. He then placed two black rhinoceroses, also with a calf, around a tuft of grass. He followed this with two large tree stumps, diagonally in line with the leopard cubs and the zebras.

A mother baboon carrying her infant on her back is to the right of the rocks, with a tree stump placed centre right. Lastly, he placed an eagle on top of the mountain.

Tom fittingly called this, “The Game Park”, as it resembles a typical African wild animal reserve. It is a beautiful nurturing tray with many pairs of mothers and their young. Following the centering of the Self, this is the animal-vegetative phase of development wherein the newly developed psychic qualities begin their ascent to consciousness. Here Tom enters his instinctive, intuitive world, activating the inner qualities he needs to live in the world in a way that honours the Self. Jung (1978) speaks to this phase of psychic development as follows:

..Intuition is a perception via the unconscious… Then there are the archetypes, those images of instinct. For instinct is not just an outward thrust, it also takes part in the representation of forms… Our instincts do not express themselves only in our actions and reactions, but also in the way we formulate what we imagine (pp. 307; 400 – 401).

While the instinctual energies are not yet conscious to Tom at the time of the making of the tray, clearly his work in the sand touches and activates this potential. It is well-balanced and harmonious. As he begins to integrate his newly-developed qualities into consciousness, Tom also maintains his connection to the resources of the underworld with the open blue waterhole. In similar ways, the sturdy baobab and the eagle connect the earth and the heavens, giving him access to what is deeper and what is higher. The baobab tree serves as a formidable beacon, and a sustaining anchor point for Tom’s presence in this vibrant world. The baobab is the largest succulent plant in the world, steeped in mystique, legends and superstition. And, as previously mentioned, the baobab provides shelter, water, food, and healing. Leafless for nine months a year – the length of human gestation, the baobab is the tree of life – she is the centre (Wickens, 2008, p. 50).

The outstanding flora and fauna of South Africa are a large part of our national treasures. In this tray, Tom has evoked the instinctive animal powers derived from their collective symbolism, and has assumed ownership of himself as an African man. Now he has a rightful place to be that he can call his own both inwardly and outwardly. Tom now knows he is the fisherman, the provider, the nurturer of both body and spirit. He is now responsible to himself and to his world.

The harmonious cooperation of the male and female pairs in his tray gives birth to nurturing and generative possibilities represented by the many babies. Perhaps Tom will now be better positioned to enter into a healthy relationship with a woman.

For the significance of animal references we refer to Brunke, 2012, who describes the features of all these African giants in a beautiful way and as follows: The elephants were the first figures Tom selected for his tray. Elephants are South Africa’s “gentle giants”. They are majestic and the largest land animal on earth. Elephants are highly intelligent, renowned for their sensitive temperaments, their close friendships and deeply-bonded family groups. They have a matriarchal social structure. When a calf is born, the whole female herd raises and shelters it. Their leadership system is preserved by a protective guardian matriarch, usually an elder and the largest cow, along with the fierce defence of the bulls. Together, bull, cow and their calf are available to accompany Tom in his journeys to the unknown, for they remember the way, they never forget. The guidance and protection of this mother elephant energy now replaces Tom’s formerly destructive animus-burdened anima, giving him the inner resources to guide his consciousness to the Self. I was moved by Tom’s positioning of the elephants near me. I could not help but think about my own mother, whom I knew only 3 years, and who has been carried by the matriarchal symbolism of the elephant since I started my sandplay journey as therapist and client. I experienced a strong feeling of transference and counter-transference here. Did my own experience of mothering in some way work to activate this matriarchal aspect in Tom?

Ancient fossils have revealed that the semi-aquatic hippopotamus is related to the whale and the dolphin. Although hippos can be very fierce, they move through the waterways, eating the underwater growth. Thus they clear the channels for the movement and flow of water. In nature, the hippos submerge for six minutes, and then return to the surface for air. Symbolically these hippos are available to guide Tom’s descent to the depths to the unconscious and safe return to consciousness. They insure that his movement through the channels of the unconscious will be clear of obstacles.

Tom is mature in age and must become so on all levels of his being. In South Africa the leopard boasts a powerful and beautiful body. It is unsurpassed in its skill at stalking and speed. The leopard is an excellent swimmer, an agile jumper, an exceptional tree climber, and is remarkably able to adapt. Perhaps the proud and solitary leopard can show Tom the honour of self-contained privacy; the pride of independence, and the benefits of objectivity.

Then, snuffing and snorting, comes another loner, the ancient two-horned, long-lipped, nocturnal, leaf-eating three-toe South African black rhinoceros. The real male, the genuine heavy weight, breaks the scales at more than one and a half tons. He holds his head high, showing off his excellent sense of smell, keen hearing, swiftness and agility. Rhinos are known to exceed the speed limit in their occasional jaunts through towns. Then just as quickly they are able to turn on a dime. In Africa rhinos are illegally hunt and mutilated for their horns. Their horns represent strong sexual power as well as healing energy. For Tom this mutilation may symbolically carry his own sexual emasculation experience. The typical South African male ‘Boer’, translated as patriotic white farmer, has a natural inborn love and connection with the wild, resulting in a fierce protection of its inhabitants. Therefore Tom’s inner rhino works here to teach him about powerful healthy sexual masculinity; when to trust his instincts; and how to utilize his inner strength. No longer is he the scared and bullied little boy. Tom now can listen to his own inner rhino voice:

… what we want to say to humans is this — calm down, go within, listen deep. We invite you to roam the deep expanse of your soul. Find us there. We are happy to talk, to recall the old days when a human and a rhino could consult in peace… (Brunke, 2012, sect. rhinoceros).

Entering from the right side of the tray is a single baboon with her baby. This female baboon embodies Tom’s responsibility and accountability toward himself, bearing the load of existence on his back, protecting and nurturing himself. She models the consideration of healthy dependency, and replaces his own wounded relationship to his mother with a healthy mother-child bond.

The gorilla is highly intelligent and shares 98% genetic makeup with human beings. The gorilla guards and protects. As in the wild, the gorilla in Tom’s tray offers his profound strength and wisdom. He is the sentinel, the gatekeeper against the dark shadow predators and disordered perceptions. At his back, on the mountain, the eagle waits in anticipation. The eagle is a regal bird with unusually large eyes and enormous pupils. The eagle’s eyes have a million light-sensitive cells per square millimetre of retina, five times more than do human eyes. While humans see three basic colours, eagles see five, giving them extremely keen eyesight. This South African fish-eagle, with its distinctive plumage, has a beautifully pure evocative “weee-ah hyo-hyo-hyo” call, known as “Africa’s song”. Tom must watch and warn, but with wisdom – as do eagles. Notably, this is the fish eagle. He catches fish, and is another embodiment of Tom, the fisherman that unites the underworld with the heavens.

Both the eagle and the gorilla are watchers and doers. The gorilla protects his position in his group, even to the death. He is determined and stalwart. Symbolically he can face the darkness and does not retreat from the forbidding shadowy places of the psyche. The eagle watches with his keen eyes and warns with his piercing call. He hunts and does battle with his strong talons and swift wings. Symbolically, the eagle transcends the mundane. His eyes penetrate beyond ordinary vision and his wide strong wings carry him to the sky. His soul is free and open. He can touch the sun and keep Tom in the light.

Finally, in the far left corner of the tray, behind the thickets, are the zebra and her foals. Known as, “…the traveller always moving, always on a quest”, zebras sleep while standing, for they are very vigilant. Zebras can be vicious and unpredictable, and cannot be tamed. They are outstandingly sociable, always staying in a large dazzle (herd), zigzagging from side to side in a zeal (group), to outpace their predators. They are exceptional for their distinctive black and white banded bodies. Each individual has its own unique striped pattern. But when this mare in Tom’s tray was to give birth, she went into hiding behind the bushes to allow the foal to bond with her smell. This concerns attachment and a healthy mother-child bond. Perhaps the protective mother zebra secluded in Tom’s tray carries the birth of a newly developed relationship to the mother archetype.

Being black and white, zebras embody dark and light, the integration of psychic elements that were formerly separate. The process of integration is also the process of individuation. Black and white symbolism refers to the integration of opposites. Here in Tom’s work he integrates what was previously unconscious into the conscious position.

As the unconscious reveals itself… (through various day to day experiences, expressions etc.), and in countless other ways (in this instance, sandplay), the archetypes emerge… archetypes belong to the deeper layers of the psyche, the collective unconscious. Since they are unconscious, we cannot observe them directly, but we can see their manifestation …in the form of archetypal images and symbols… The individuation process is a path to self-knowledge (Singer, 1994, pp. 133-134).

This is the path that Tom walks. It is the process of individuation. Through the archetypal energies of his animal symbols, the vitality of Tom’s own instinctual animal-power emerges on his journey to be whole. In Tom’s own words, he is truly “finding myself”.

Tray 10 5 Weeks later

More than a month had elapsed since Tom’s last tray, given the intervening Christmas and New Year holidays. When we met for this session, he seemed well and rested. Apart from friendly greetings and a short conversation about generalities, Tom did not mention anything noteworthy, except wanting to do his work in the wet tray.

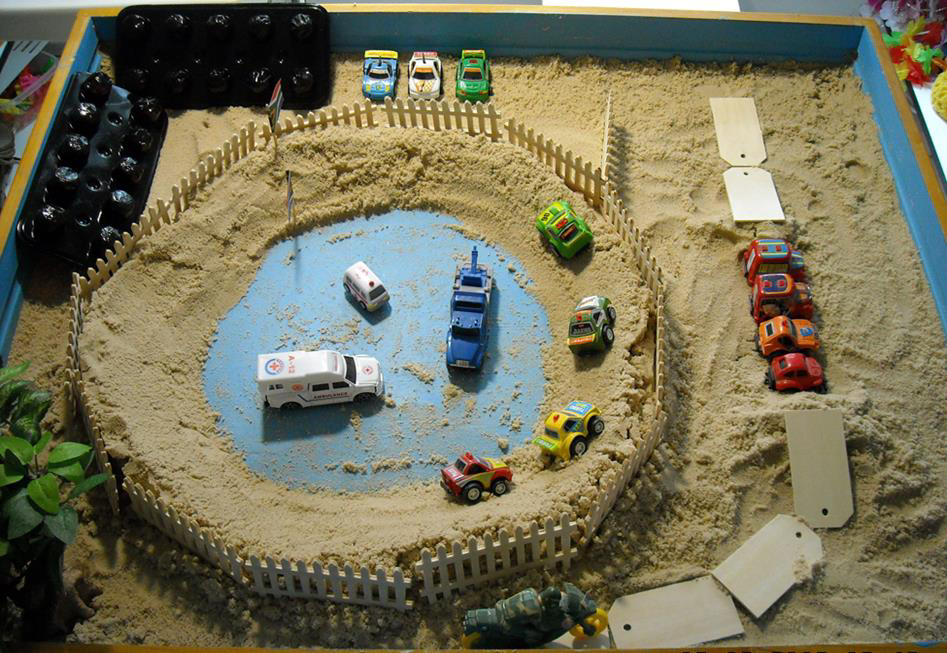

As usual, Tom began by preparing the sand, ruffling it into a course but even flat surface, after which he selected the black barricades from Tray 1. With them he formed two squares in the tray.

In one section Tom aligned ten Defence Force officers into three rows, facing the front of the tray. With the exception of one officer at the far left, all of them rigidly stand at attention in front of a powerfully stern sergeant.

Tom then built a firing range using thin wooden tags as targets. He put five men squatting behind the sandbag gun-rests, aiming their rifles at the targets. He put two helicopters in the far left enclosure and a flattish yellow-green box in the far right corner, serving as a weapons depot, shelter or bungalow. Lastly, Tom stood a blue uniformed officer or policeman, possibly the traditional obligatory Safety Officer, behind the riflemen.

When the tray was completed, Tom commented that he preferred order and discipline, and that he felt “excited and positive”.

The image of order and discipline, and an apparently optimistic absence of fighting, seem to be exactly what this tray is all about. The officers at the back are not wearing “brownies”, their camouflage outfits, but their “step-outs”, full dress uniforms. The men at the shooting range are practicing their sharpshooting skills. The fact is that they are defence related and they are practicing.

In his Tray 10, Tom enters the second developmental phase in the progression toward consciousness. Dora Kalff called this the “battle scene”, where both the positive and the negative poles of the newly developed psychic qualities separate and become conscious. By so doing, Tom’s newly activated qualities of positive mothering and anima energy, his strength as a man and his sexuality are integrated into consciousness in their fullness. Tom will be aware of and have access to the full range of the positive and negative aspects of the pertinent archetypal material. In this way he will no longer be a victim of the darker aspects of these qualities in himself and others, but will be aware of their presence and able to clearly see them for what they are.

Tray 11 1 Week later

Tom began his eleventh sandplay with firm movements. Unlike the surface ruffling he had done before, here he quickly gathered all the sand at the centre of the tray, forming a round island surrounded by a pure blue deep sea. He first added the trees, bushes and the ring of ivy making a dense forest that covers the upper left portion of the isle, leaving an open area at its right, upon which he beached a row boat.

Tom placed a mountain in the forest on the left side, and the tree stumps at the right. Tom then nestled two large rocks near the far side of the island, forming a small recess between them. He completed his tray by seating the fisherman near the rocks, placidly facing the water.

Here the fisherman returns, now sitting quietly in isolation on his small island. He appears content and at home, waiting silently, looking across the clear still ocean. It feels as if he is meditating. The previous tray was filled with masculine energy, this one is more feminine. It feels uplifting and carries a positive sense of conservation and nurturing of life itself. This tray radiates a profound sense of serenity and stillness. When Tom was finished, he again confirmed that he is the fisherman and declared this tray to be, ”…a get-away place”, which he was taken with, as it gave him “…a feeling of peace”.

By shaping his island, Tom has temporarily separated himself from the mainland. This is a significant part of his individuation process, as he now has his own identity. The small boat stands ready for the passage between the island and the surrounding land. Here Tom takes ownership of a rich part of the psyche. He is no longer lonely; rather he is able to be alone, at peace with the wholeness of himself. Tom can and will survive. The fisherman has a life-boat; he may come and go to his island as he chooses. He will always have free access to this place, for it is uniquely his. Tom has become his own man – he has truly “found himself”.

Tray 12 2 Weeks later

As in the previous session, Tom started by firmly moving the sand. Now creating a smaller island encircled by a ring of water surrounded by a mainland. He then linked the island with the outer area by means of a large bridge.

Tom added broad leafed trees to the island and mainland, and positioned tree stumps and a fir on the island. He then placed the fisherman near the right side of the bridge footing. Next he added a medium size rock, and finished with three boys playing a game at the centre of the tray.

Here Tom creates a circle within a circle, squared by the boundaries of the tray. This is the ego aligning with the Self. This is the perfect mandala, bridging what is inner to what is outer and further integrating his psychic development. The fisherman’s reach into the depths is now integrated with his conscious life; it is apart, yet connected.

In the centre of the tray the three boys play as they do in the schoolyard, while the fisherman continues his daily life. The sanctity of the inner world is integrated into ordinary life.

A large bridge connects the two worlds of individuality with humanity as a whole.

In the course of Tom’s individuation process, he has not only bridged his own existence to the Self, but now to his fellow-man. This is reminiscent of the famous saying, “No man is an island sufficient unto himself. Everyone is part of the main… ”.

Tom said the tray reminds him of school when they had an island on which they could play. This was not a regression, but a step back to the innocent years prior to the onset of his chronic wounding. Singer (1994) says “Suffering human beings come into analysis. (In Tom’s case this is sandplay therapy). They need to be made whole again. They need to be reunited with that from which they have departed… ” (pp. 240-241). Tom has reunited with those lost parts of his innocence and is now liberated to live life fully.

Tray 13 1 Week later

The work began with Tom creating a large central circle surrounded by an ample bank.