21 February 2016

By Dr Celia van Wyk

God grant that I may live to fish,

until my dying day,

And when it comes to my last cast,

I then most humbly pray,

When in the Lord’s safe landing net,

I’m peacefully asleep,

That in his mercy I be judged,

As big enough to keep. (Circle, H. 1915-2012)

A true fisherman is one who will persist at his task for hours, on the mere possibility of making a great catch. Mark told me that his wife would sometimes ask him, “How can you stand there in the water for hours, hoping to catch a fish?” His answer, which any fisherman can identify with, was, “Easy.”(Deffinbauch, 2004, Introduction section, para. 2).

In my home country South Africa there are a few traditional fishing villages, which includes Kalk Bay, Kassiesbaai, Simons Town, Struisbaai and False Bay. These communities mainly consist of self-sufficient ethnic groups derived from a mixture of different cultures who migrated to South Africa in the early 1700’s.

The fishermen of these communities go out early mornings with their fishing crew in boats, and come back late afternoon, where their catches of the day are thrown from the boats. Selling transactions happen in a lively way on the beach just after the catches are hauled in. The fish are then sold to other people of the community or holiday goers who are gathered on the beach for this, or taken home to their families.

Generally fishermen, especially in rural areas or fishing communities are seen as poor people, who are dependent on the sea for eating and existing. Over decades this status was maintained universally.

Fishermen at Bronze Beach, Northern Natal, South Africa, December 2013

During December 2013 at Bronze Beach where my family and I enjoyed our Christmas holiday, I spoke to a few fishermen one early morning. They told me their catches go either to their families, or they give it to “people who need it”. They don’t throw the fish back into the water. Also they fish not only to provide food, but also because they enjoy the act of fishing, being alone by themselves, and enjoying nature in so many forms.

Some fishermen have different status, which is based on their reason for fishing. This activity can be devided into two main groups, namely fishing for a living (commercial), and fishing as a sport activity (recreational). The latter has the status of exclusivity, adventure and carries a respected image.

When I think of a fisherman, the image of my father comes to mind. As a little girl I always went fishing with my dad. It was a natural part of our lives, always filled with feelings of excitement. I remember my Dad’s fishing clothes, his fisherman’s hat that covered the back of his neck with a long material flap, his fishing-rod, the bait he made from “pap” (a mixture of maize meal and water clumped together in a little ball) and hook, and I remember my father’s relaxed smile, and the joy this hobby provided him.

Becoming a young lady, my view on fishing changed. I developed sympathy for the fish caught, and was not interested to hear about the ecological value of fishing, or to see how fish was caught, followed by huge struggling and squirming to get away, just to be thrown on a heap, later to be beheaded and slaughtered.

Years later, as a married woman, I realised my feelings of appreciation for my husband not having fishing as a hobby. Interestingly though, one of my favourite figurines in my sandplay collection, also very popular amongst my clients, and used over and over again in sand trays, is a little Chinese fisherman made from Shiwan ceramics.

Fisherman from my sandplay collection

In the Chinese community the little mudman fisherman is a well-known product of Shiwan arts and crafts, and the symbolism of it is vague in the culture. It seems to be related to the meaning of self-reliance and the seeking of good fortune. This supports the strong symbolism of fish in China portraying fertility, abundance and good luck (Tresidder, 2006).

The fisherman is an archetypical symbol and carries similar symbolic meanings and energies universally. However, it may have different significance for different cultures and the time frame of its existence. Fishermen are found in various religious groups’ scriptures. The astrological age of Pisces commenced with the birth of Christ, which put great emphasis on fish and fishing during that time.The Apostle Peter was known as the Fisher of Men, and in the Christian Bible we find eight verses about fishermen. They formed a distinct class which represented patience under difficult and strained work circumstances, huge tolerance to harsh weather conditions, strength, endurance, fearlessness and dauntlessness, signifying strong masculine energy (Luke 5:2, 5; 9:49, 54). They were also known to be rough in the way they treated others and being crude in their manners and their speech. Here we are confronted with some of the shadow energies of the fisherman.

To study the fisherman we need to remember that fish ubiquitously carry rich and strong symbolism. According to O’Connell, Airey & Craze (2007) fish represent the truth and faithfulness in Hebrew religion, and in Hindu myths it plays a saviour role. Shepherd & Shepherd (2006) mentioned some of the meanings of fish in different cultural setups too, as follows: ICHTUS, the Greek word for fish or fisherman was seen as an acrostic for Christ’s name as it relates to Jesus Christ, God’s Son and Saviour. At the Jewish Passover eating of fish represents food of paradise. The word fish acquired Eucharistic symbolism from the miracle in the Christian Bible when 5000 people were fed with five loafs of bread and two fish; and it is said that a fish or pair of fish which appeared on the Buddha’s Foot, frees one from desire. Jungian symbolism refers to fish as the spirit, and Jung (1959/2008) himself referred to the “edible fish” as a “wise friend” (p. 146). Furthermore fish is a phallic symbol portraying sexual happiness and fertility (O’Connell, Airey & Craze, 2007).

Fish as animals in water signify a direct link with the unconscious. They symbolise cyclical birth and rebirth. By fishing the fisherman reaches deep down into the unknown world of the nourishing waters, not knowing what he is going to find, but focusing and trusting that it will be good. In the waters a fish follows a cycle of birth and feeding from the waters. It sacrifies its life at the hand of a fisherman or in another way, and through its death feeds the fisherman or others, thus providing nourishment from the content of the deep waters. Fish spend their entire life cycle in the depths of water. Through their contact with the water and their role as nurturing element, integration happens through decomposition when it returns to the source biologically. Jung stated (Steinhardt, 2013) that “As the fish can say “I am the sea,” then the sea can say “I am the fish.” (p. 150). This reciprocal relatedness of all things engenders a cyclical rebirth. As nurturing elements, its death and decomposition return its material body to the source waters. In this sense the fish is one with the waters, with the depths.

In the individuation process a person reaches into the mysterious but rich collective unconscious when the limitations of the ego force a psychic standstill and a decent to the depths. This is a deeply nourishing and psychic healing journey that, as in the life cycle of the fish, results in a sacrifice of the old wasted matter. An integration with new psychic aspects needs to happen, in order to receive the gift of the rebirth of individuation. Goldsmith (1973/2011) mentioned that spiritual healing is brought about through the realisation of the Christ in individual consciousness. This only happens through the alignment of the ego with the Self. The ego’s integration of more and more of the Self carries the spirit of divinity, thus Christ.

Jung (1959/2008) explained the phenomenon of rebirth beautifully by his illustration of the story of Moses and his servant Joshua ben Nun, which is a name for fish, suggesting that he was born in the dark, unknown waters. Joshua acted as the shadow which needs to be confronted to gain knowledge from the unconscious. The two men took their fish with them as a “humble source of nourishment” (p. 139) on their journey to find the place where the east and west seas (the known and unknown) meet. Here we see a man and his shadow on their journey towards integration and individuation. They did not keep their focus on the fish (their knowledge source was not yet utilised). When the fish jumped out of the containing basket Moses and Joshua carried, Jung compared it to the loss of the instinctive part, the unconscious discovery of the source of life. The fish, as he described it, is a “content of the unconscious” which supports re-establishment with the source, the origin through the contact with the water again. And as described above, with this re-establishment, rebirth takes place. The fish thus again becomes part of the unconscious.

From the fisherman’s perspective eating fish leads to an inner feeding which helps the fisher’s body to grow and be healthy. By eating fish a consolidation takes place between land and water, fisherman and fish, fish and matter.

Fishermen are also present in numerous folk tales, myths, stories, fables and fairy tales, mostly as the main character in each. McMurray (1995) stated that: “All collective bodies have myths and rituals that preserve their continuity” (p. 9).

In Chinese mythology we find the beautiful and rich stories of Fu Xi, a serpent-bodied culture hero and ruler, and his sister Nü Wa, who later became his wife. Fu Xi taught his people many wonderful skills. One of them was how to fish using a fishing net after he saw how intricate and effective the spider weaved his web. Fu Xi made a net that his people could use for hunting and fishing, and this skill was later passed on to his offspring.

Fu Xi is described as a godlike person who could move between earth and heaven (Allan, 2000). This ability and his serpent body carry the masculine principle vertically, rotating around an invisible axis. In this way the serpent functions as a connection between heaven and earth. His fishing and teachings on how to fish bring the conscious and unconscious together, still on the vertical axis, at a crossing point in the water, where the fisherman forms the central ego-self axis. Fu Xi can also be seen as a primordial character in the instinctive serpent part, and because of his divine character, he carries the symbolic energy of the Self.

In Fairy Tales we find a sweet German story collected by the Grimm Brothers called, “The Fisherman and his Wife” (Phillips, 2010, September 5). [Video file]. Another similar delightful story comes from Russian Folklore, namely, “The Fisherman and the Golden Fish” (Tsekhanovskiy, 2011, December 20). [Video file]. In both stories the wife was never satisfied with what life offered her. She represents the undeveloped anima of the fisherman. The fisherman represents the limited ego needing to change and move towards the richness of individuation, and the fish represents the knowledge from the unconscious needed to utilise this action. The conflicting opposites between man and wife create a great tension between them. We might expect the transcendent function to be activated by this tension. But in these tales the tension cannot be held and the result is inflation. The wife is not able to hold the pressure due to her unrealistic expectations from the fish projected on the fisherman.

A well-known Pulitzer-prize story is Ernest Hemingway’s, “The Old Man and the Sea,” which is about a 3-day long battle between an 84-year old fisherman, Santiago, and a big marlin; the marlin’s surrender to death; and the eventual loss of the dead fish to the sharks following them to shore. The old fisherman’s struggle to overcome his own physical and psychic weaknesses in his effort to conquer the strength of the big fish through endurance and courage is at the same time a focus on his masculine energy. The reconciling factor thus is his refusal to give in to either the fish or his weaknesses. Because of the strong psychic energies held by the two parties, the fish and the old man, transendence occurs. It is also a story about soul-searching, which is linked to spiritual energy, and is part of the fisherman’s individuation process to become aligned in his own truth. Baker (2011) accentuated the strong Christian line in the story, and the battle between the old man and the fish during this soul-searching journey. In the symbolic synopsis of the LitCharts Editors (2007) the marlin’s symbolic value comes through in the fact that it represents the fisherman’s ego, thus his struggle with himself.

Oscar Wilde wrote, “The Fisherman and his Soul,” the story of a fisherman who loved a mermaid, but because he had a soul, she told him they could not be together. He cut out his soul. After a year-long struggle with his soul, who wanted to reunite, he gave in to the request. Unfortunately his heart was still with his mermaid, and his soul could not enter his heart. McMurray (1995) described “Soul” as “containing the faculty of relatedness to the gods and goddesses” (p. 206). When someone rips out his own soul it means rejection of the Self. Essentially this has to do with not honouring one’s own divinity or spirituality. It is a dark shadow component, and a descent into the depths. McMurray continued to state that soul is also a, “…non-ego personality that participates with the archetypal energies, bringing them to consciousness through personification” (p. 206). This implies that the fisherman needs to humanise his soul through unification with his heart. For this he needs to sacrifice his anima, the mermaid, and himself through his broken heart before integration and new birth can/will emerge.

One of the most varied legends, abundant with symbolism, is that of the “The Fisher King” or “Wounded King” disguised as a fisherman. The Fisher King was first portrayed by the 12th century Chrétien de Troyes. After this it was featured in Celtic mythology and medieval works, followed later in Arthurian times with the legend of Lancelot and King Arthur. In more modern times this theme continues to appear in many more stories, works and theatre plays. The Fisher King was always pictured as the archetypal wounded masculine. This is represented by the location of the wounded area near the genitals. The wounding also implies the sacrificial wounding of Christ. The fisherman was doomed to fish, thus forced to introspection and self-reflection as this is the only activity that relieved his pain.

His injuries and resulting impotence had a huge effect on his people and kingdom, ultimately resulting in a realm of infertility and empty wasteland. According to Bregman, (2012) balance could only be restored if he could integrate his wounded masculine with a feminine principle. In the story this is represented by the Holy Grail, a female symbol, but also one of sacrifice, a “…cup containing the blood of Christ, caught at the Crucifixion, by Joseph of Arimathaea,” as described by Hall (2003, p. 94).

In Brazil there is the legend of the black Madonna of Aparacida who came out of a river in the net of a fisherman while he was fishing with his two friends in 1717. The Madonna wore a blue coat and was the most feared Madonna in Brazil. She represents the strong feminine energy whose presence brought abundance. On a conscious level the fisherman realised it was their holy patroness after he cleaned the statue. Thus with this act of recognition, the fisherman integrated the feminine energy with the masculine (Turner, 2013).

Nearer to home from a tribe in Southeast Africa there is a delightful short story called, “The two fishermen’s house.” The story was told by DeCee Cornish of Fort Worth, an African American storyteller to Grace (2011) and it goes like this:

Day Fisherman and Night Fisherman. Day Fisherman finds a nice spot and draws plans for a house in the sand. Goes home. Night Fisherman comes along, sees it, thinks the sun drew the plans and left them for him. Gathers poles for a frame; goes home. Day fisherman comes back and sees the poles, and thanks the Moon for helping him. Builds frame; goes home. Day and night the two men build the house, each thinking his partner is the moon or sun. When the house is finished, the day fisherman moves in. That night, the night fisherman finds him in “his” house and they argue over the ownership of the house. Take case to judge. Judge listens to each’s story, then says: The house does not belong to you or you; the house belongs to the land (para. 2)

Here we find the spontaneous flow of interconnected thoughts and images between the two fishermen around a specific idea, in this case the building of a house, which is an indication of the Self. There is strong tension between the opposites of masculine and feminine energies, sun and moon itself, night and day, shadow and light. The ego seems to overtake the cause, which leads to a state of possession.

And then there is the tale from West Africa called, “Anansi goes Fishing,” about a spider, “Foolish Anansi,” and his wise friend, the turtle, who decided to go fishing together. Lazy Anansi tried to trick Turtle into doing all the work, but Turtle outwits Anansi everytime until Anansi finally realised he cannot trick a fisherman. In the process however, Anansi learned valuable skills of providing for himself. The symbolism in this story centres round the trickster energy and the wise soul energy of Anansi, which is a duality providing the view of both hero and villain in himself. According to Ferguson (1995), Hill (1982) described the trickster energy as being a dual force: able to be light and positive, powerful, wise, charming, brave and strong, but at the same time it can be dark and negative, dumb, deceitful, disloyal, cruel and selfish. Nevertheless is this a beautiful story about individuation. The Anansi stories are from West African oral folklore. The symbolism of a spider’s web is explained on the internet blog (Heroes 2011, Edublogs, 2010) as, “…an archetypal symbol of the weaving that brings form into being; laying a foundation for a new cycle of growth.” And “…spiders in their ceaseless weaving and killing, building and destroying, symbolise the ceaseless alternation of forces on which the stability of the universe depends.” (p. 4, para. 6)

Dr. Jung himself had some referrals to the fisherman as an archetypal symbol. One we find in his reflections (1961/1995) where he wrote about a dream his son Franz had at the age of 9 during a series of parapsychological events in their house in 1916. Franz drew a picture the next day. In the middle of the picture was a river, with a fisherman standing on the shore caught a fish. The fisherman had a chimney with flames and smoke coming from it on his head, and above him he drew a hovering angel. On the other side of the river he drew the approaching flying devil, who was furious because his fish was stolen. The angel told the devil that he could not hurt the fisherman, who only caught bad fish. We here experience confrontation on an unconscious level between shadow and light and strong tension of the opposites between devil and angel. In addition there are vertical-horisontal and ego-Self axises connections between the river, the shore and the fisherman with his fishing line.

In 1923 Jung recalled this dream to his friend and translator Cary Baynes. Baynes replied, “…The next day you wrote out the “Sermons to the Dead, and … I knew you were the fisherman …, and you told me so.” According to Baynes Jung identified himself as an incarnation of the legendary wounded Fisher-King. These are notes from Baynes about her discussions with Carl Jung who was her mentor, written in the form of letters to Jung, but never sent (Samdashani, 2009, 205b).

Turner and Unnsteinsdótter (2011) mentioned that fish carry intense energy of the possibility and need for a renewal in spirit. Jung himself understood the laws of the universe, and realised that the Piscean age was followed by the Fisherman, Christ, whose religion was symbolised by fish and fishers of men. Because of the principles of astronomy, this would naturally be followed by the age of water, or Aquarius.

Eliade (1971/2005) stated that archetypes and archetypal gestures, happen in “ …mythical time, at the extratemporal instant of the beginning.” He further explained that “…everything in a sense coincided with the beginning of the world, with the cosmogeny. ”These “happenings” became “…examples for humanity, because they revealed a mode of existence of the divinity, of the primordial man, of the civilizing Hero” (p. 105). As an archetype, the fisherman also coincides with the beginning of the world, through its connection with the fish, which carries the symbolic meaning of beginning, birth and rebirth. Both are powerfully part of the divine existence and the cycle of life.

On a conscious level the fisherman feeds himself and others, and his fishing symbolises caring and nurturing to sustain life and survival of himself and the ones he feeds. On an unconscious level his ego makes contact with the unknown, the divine, and this energy leads to the unlocking of dormant potential abilities, followed by transformation. This involves the dissolving of the old nature, self-undoing, and letting go of defences and boundaries. Eventually rebirth and connection with the Self happens. It also implies feeding and nurturing on the unconscious psychic level, referring to fishing for knowledge, growth and transformation.

According to Steinhard (2013) there is a connection and relationship between the fisherman’s external quiet composure and his psyche’s inner creative potential and movement. Looking further to the act of fishing the fisherman can be depicted as the visible conscious ego trying to connect with the invisible unconscious spirit through the vertical axis, represented by the fishing rod. The meeting of this vertical axis (fishing rod and unconscious) with the horisontal axis (earth and conscious) forms a strong crossing of which the fisherman is the centre, thus creating the connection of ego-self axis. We also experience a strong holding of the tension of the opposites through the realm of the fisherman’s quiet and patient waiting with the follow-up of sudden action and gratification through the catching of a fish.

Furthermore the fisherman seems to hold everything together, from his body on solid ground, and his arms a part of this body, holding the rod and line, which is connected to a hook and bait, which is connected to the waters, which is connected with what is going on underneath the waters. With this we realise the catch always returns to the source, whether it is through feeding the fisherman (nurturing the psyche), or returning to the deep nourishing waters of the unconscious to plunge into a state of decomposition, in order to start all over again. Steinhardt (2013) referred to it as the fisherman’s rod forming a link to a possible relationship with a fish in the water.

The waters in which the fishing takes place can be seen as the collective unconscious, where all sea-life is held, and psychically where archetypes exist. Because water has a strong healing and regeneration element, the act of fishing can be like a baptising, promising and providing balance and inner health on a physical, emotional and spiritual level. McMurray (1995) explained the term “world unconscious” very well and as follows: “In allowing ourselves to be drawn into the environments that we inhabit, we begin to experience nature as teacher – nature as healer” (p. 137). Therefore we can say that the fisherman is related to all of us not just as a fisherman, but as the way nature works. Everything goes back to the source of creation.

As with archetypal symbols, the fisherman needs to fulfil the requirements of an archetype in a dual manner, through its existence in the world and it’s experience in the human psyche. Turner (2005) referred to this phenomenon as the archetype that acts as the “spiritual guide for the psyche’s material instincts” (p. 25). As we have seen, the archetype of the fisherman, like all other archetypes, carries powerful amounts of psychic energies.

Another important energy present in the fisherman, is the energy of its own opposite, its dark side. This shadow acts as the trickster, by offering tasty food to the fish, only to catch it imprisoned in the net or on the hook, to be killed afterwards for his own gain, profit or welfare, or to be thrown away or back in the waters, wounded. The hook carries the symbolism of helpless entrapment. A fairytale compiled by Parker (2011) as retold by Lang (1898) illustrated this beautifully in the story of the fisherman who was very poor, and one day when he went out to fish, his first catch consisted of a carcass, the second catch was a large basket full of rubbish and the third catch was full of mud, stones and shells. He tried a fourth time and caught a yellow vase with a genie inside, which he freed, but the genie wanted to kill the fisherman who saved him, to break the spell of the King of Genies. The fisherman outwit the genie by tricking him into the vase again, and sealed the lid (p. 220-227).

Although the fisherman seems destructive in some ways, he always sorts his catch, which provides him the image of a Christlike divinity and spirituality. Ezekiel 47:10:

And it shall come to pass, that the fishers shall stand upon it from Engedi even unto Eneglaim; they shall be a place to spread forth nets; their fish shall be according to their kinds, as the fish of the great sea, exceeding many.

Fontana (2010) described this divinity of Christ as follows:

Since the dawn of consciousness, humankind has been awed by the mysteries of the cosmos, the natural world and life itself. This fascination gave rise to the idea of divinity, a power beyond nature that shapes and controls the universe and human destiny (p. 105).

He further emphasised the fact that Christian faith was often symbolised as a fish, which was until the fourth century a more common symbol than the cross. And he also mentioned the associations of the fish in Christianity derived from the several gospel episodes concentrated on fish and fishing, the calling of fishermen as disciples, the miracle feeding of huge crowds with small numbers of fish, the draught of fishes symbolising the growing church and the coin found inside a fish to pay the temple tax. He continued describing the divinity of Christ as follows:

Given these (fish) associations, it is hardly surprising that Christ should often be represented as the “fisher of souls,” and the fish becomes a symbol of Christ himself, initiated in water through the sacrament of baptism, Christians are Christ’s little fishes (“pisciculi” in Latin), and the font in which they are baptised (originally by full immersion), is literally the “fishpond” (Latin “piscina”) (p. 72).

Fontana concluded that the fish is also a symbol of St. Peter, by Christ designated as the “fisher of men,” and of St. Anthony of Padua, who is said to have preached to the fishes. We thus here have a symbolic cross formed of a vertical and horisontal axis with a meeting point in the middle; with Christ as the fisher of souls (centre and connection of the ego-self axis); St. Peter as the fisher of men (horisontal axis); and St. Anthony as the preacher of the fishes (vertical axis).

In sandplay therapy the fisherman may symbolise the need to connect with the unknown, the unconscious, and the willingness to “fish” this rich psychic content to consciousness. This happens only when the psyche is willing to work on a deeper level, ready for progress towards integration with the already “known” level of consciousness. Howe (n.d.) referred to fish as, “…psychic content living in the depths …… elusive, mysterious, and a nourishing treasure that is wisdom.” Thus is the fisherman the reaper of this wisdom, and by the act of catching, or eating fish portrayed in a sand tray, the integration happens.

Furthermore the use of the fisherman in trays may also symbolise the “need to know,” in other words, obtaining most inner knowledge to support movement towards the Self.

Steinhardt (2013) mentioned that she found her clients mostly use the fisherman symbol once during their processes. It seems generally true in my clinic as well. However I had a client who used this symbol in 9 of his 26 trays. For this young man, age 24, who came to the clinic for issues of poor self-esteem and “to figure out who he is”, the fisherman carried tremendous value and powerful symbolism. It guided him toward inner knowledge and provided a rich, life-giving relationship with the unconscious. Not only did he use the fisherman in his trays, he voiced his special connection with the figure, who also represented wisdom and tranquillity for him.

Tray 6:

In this session he used the fisherman for the first time. There’s a feeling of order and balance, with lots of triangular patterns concentrated towards the middle of the tray with an indication of the process coming to the centre. In the tray we can see there is clear access to and movement all around the water area. In the far left corner a snake can be seen sailing up into the tree. This gives the feeling of the rising spiritual feminine kundalini, a serpent from the Hindu religion symbolising dormant energy awakening into an inner spiritual movement towards enlightenment (Fontana, 2010). The use of the fisherman in this tray was the first sign of the client’s willingness to work on a deep unconscious level. We conclude this due to the accessible blue and the bridging effects of the fisherman and his rod connecting conscious and unconscious with each other. Kalff (2003) talked about fishing as the symbolic act of bringing contents from deep within the unconscious to the light. Estés (1994) explained that the nourishment gained from the unconscious waters by the fisherman is filled with “the entire elemental feminine nature,” which includes the cycle of life-death and life-nature, as death is always part of new life beginnings (p. 139).

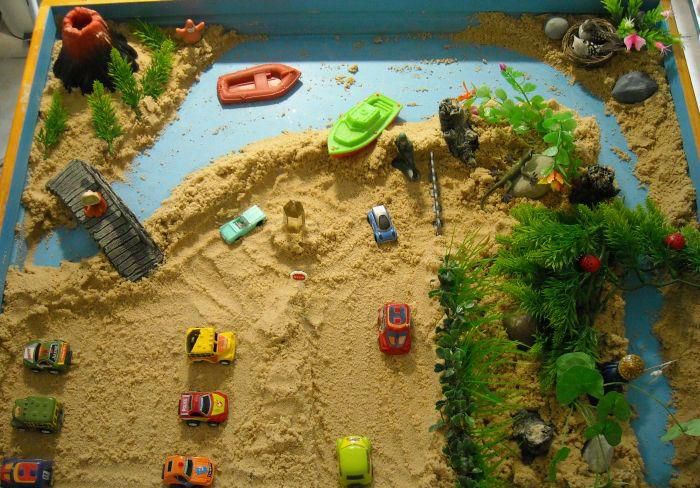

Tray 7:

This was the second time the fisherman appeared in the client’s process. It seems as if he is still testing the depths without going there yet. There is more energy present in this tray which is indicated by the cars’ movement following a road, the rowing boat in the water and we see signs of a fire emerging in the form of the volcano. The fisherman looks very separate from the rest of the tray, but is a significant part of it, as he is continuing to fish for knowledge content from the unconscious, which would later, at the psyche’s right time, integrate with conscious aspects on standby portrayed behind him. We experience more palpable energy from the volcano, which is at the same spot as where the rising kundalini showed up in the previous tray.

This is a very masculine and energy-filled tray. Turner (2013) portrayed a fisherman from Kalff’s collection, who had his fishing line down to the water. She explained it as follows: “This is the masculine that begins to fish out of the unconscious, instead of moving up to his head. It is very interesting that the masculine begins to change and to reach into the depths” (p. 274).

Tray 8:

Here we see a centering of the Self indicated by the square, circle, and triangles; thus the “wheel of life” with the fisherman at the hub. Utterly beautiful! In this session the client voiced his newly-found connection with himself and his feelings, very palpable in the tray. He IS truly the fisherman, and he knows it. The connection is now real, in balance, on a deep, spiritual level. The tray feels numinous and the eight triangles enhance this grounding in spirit with the fisherman at the crossing in the centre. Chalquist (2007) named the mandala a “magic circle” and described it from Jung’s works as follows:

A symbol of the Self “seen in cross-section,” of wholeness, of psychological totality, balance, and of centering. Has a clear periphery and a centre and is often build on the quaternity archetype. A protective circle (temenos). Circles, squares, and multiples of the number four or eight represent this wholeness. (section mandala)

The symbolism of eight triangles in a mandala is explained as follows on the internet blog (Heroes 2011 Edublogs, 2010, June):

…stability, harmony and rebirth associated with the resurrection; it resembles the sign for infinity and indicates the limitless spiralling movement of the cosmos; the inexorable turning of the wheel of life; it is a symbol of wholeness as it is two fours, the preeminent symbol of Self.

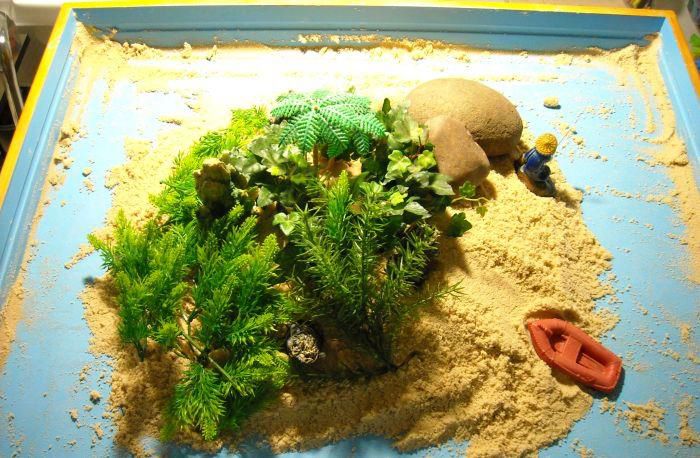

Tray 11:

The fisherman did not feature in the two sessions after the centering tray, but brought back in the 11th tray. This tray gives the feeling of consolidation of the sense of the Self. With the lifeboat the fisherman can go to his island out of own choice, and return to his home, of own choice. He has access to the place that is uniquely his. Now his fishing gives another dimension, one of further seeking, and descending into the unconscious again, with the difference that his basis, the island (horisontal axis), and the fishing line (vertical axis) are strongly connected within his own psychic boundaries.

Tray 12:

In Tray 12, three boys play ball in the marketplace, while the fisherman continues to go about his work. A bridge connects the consolidation of the sense of the Self from the previous tray. The fisherman remains at work, even in the normal day to day life situation. There is a feeling of tranquillity and balance, as the fisherman’s reach into the depths is integrated into his ordinary life. The distance, but at the same time, connectedness, of the fisherman with real life around him experienced in tray 7 thus reached integration in this tray.

Tray 14:

In tray 14 there is a more remote feeling regarding the fisherman, as if he is moving down to a deeper level, accessing more unknown territory within his psyche. There is a feeling of spirituality, which gets enhanced by two wise men in the tray opposite the fisherman. The act of fishing also feels more concentrated, with heavier, masculine energy. We experience this due to the “feeling emotion” of the tray, the dense vegetation used, the small opening to expose some blue in front of the fisherman, the wise men of the east, a far and unknown place from the west, and the eagle in a tree overlooking the scene on the left side of the tray. Some of the powerful symbolism of an eagle indicates the ability to see, illuminate and connect to hidden spiritual guides, gaining wisdom and knowledge and leading to healing and grace. Turner (2005) referred to it as the masculine principle connecting to the heavens. All of the above indicates a descent to a deeper unconscious level of the psyche.

Tray 18:

In this tray there is juxtaposition between the beautiful quiet fisherman, who’s reaching down catching his spirit and the dark shadow elements in the tray (Harry Potter dragon and the black lizard). The fisherman seems to access another scary level of darkness in this tray. Although these elements seem really terrifying, as if from very deep and old wounds, the fisherman is protected in a profound way by the wall of trees, as well as the arsenal of weapons behind him, which seems ready to use if needed. The strength obtained from all his fishing tray after tray can be seen in the bridging available between shadow and light. He needs to integrate his shadow with his light, to incur his real truth, and he needs to do this through the connection with a feminine principle, here represented by the rowing and sailing boats in the water. Now he has the inner power to do and handle it. And he is safe. Crowley (1999) equated what we experience in the tray with the stages of alchemy. We feel a nigredo-like stage, the confrontation with the shadow.

Tray 19:

By looking at the tray it feels like a death procession for a part being lost forever, a funeral boat down a birth canal towards the very core of existence of the client (which is also the fisherman). And this journey is being witnessed by the fisherman in a silent manner. There are fish around the boat, which may symbolise a sacrificial journey, but with the spiritual component of something that needs to die first before a new divine birth. There seems to be a strong holding of the tension of the opposites here between the fisherman fishing and the seemingly dead prince in the boat. Levy (1999) explained Jung’s theory on it as follows:

This is the creative tension which creates the pressure in the alchemical vessel. This pressure is the necessary ingredient for the process of transmutation of impure to pure elements in the psyche to successfully occur…….. symbolically this is a veritable crucifixion. This is to be genuinely imitating Christ (par. 2, 4).

In this tray we experience the alchemical albedo-like phase by the suffering portrayed through the vessel down the canal. The red boat is in stark contrast with the black and white suit of the prince in it, and we get the feeling of the rubedo stage too, a sacred marriage between the ego and shadow in the previous tray, and the persona and anima in this tray.

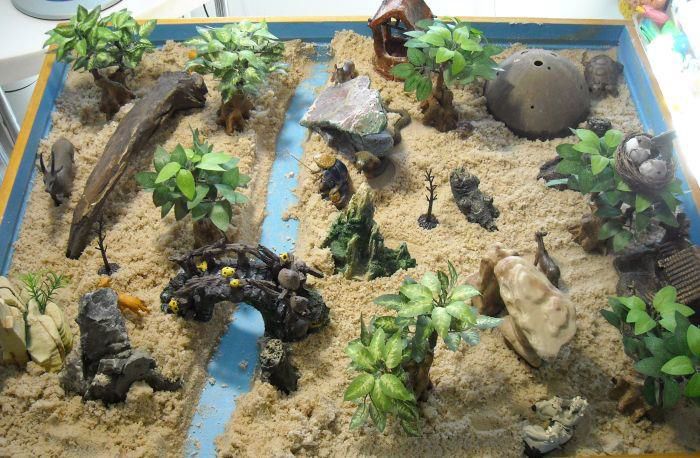

Tray 24:

In Tray 24, a large cobra approaches the fisherman from the rear. Seen as the kundalini, the rising spiritual energy in the Hindu tradition, there is a strong powerful potency received from the snake behind him. This serpent energy was also seen in tray 6 where it started to rise in a tree, and now it fills the fisherman with such beautiful force. The feeling in the tray is of tranquillity filled with wonderful energy, and if one looks at the client’s process thus far, the realisation came that the tray gives the message from the fisherman that he can just be himself, with his resources, new possibilities and wisdom gained from the depth of the waters, the unconscious (“I can just be me”). The client finished his process soon after this, and this was the final time he used the fisherman.

He followed the psychic journey necessary to reach individuation by trusting the process, reaching into the depths, incorporating his anima principle, confronting his shadow, sacrificing old parts of himself, empowering his masculine energy, and finally integrating his unconscious treasures with his conscious wisdom, to expose and reveal himself, as his “Self.”

We can compare this tray with the fourth stage of the alchemical process, the opus magnum stage, where masculine and feminine energies are balanced, and a new consciousness born (Crowley, 1999). This conclusion can be seen in the feminine antelope, serpent energy and nesting birds and the masculine house and deer he used in the tray.

The fisherman fulfilled his role as the seeker of the truth from deep within the collective unconscious, the two of them are forever integrated, they found their wisdom, and they are home. He is home. He is the fisherman.

References

Allan, T. (2000). Myths of the world. The illustrated treasury of the world’s greatest stories. London, UK: Duncan Baird Publishers

Baker, A. (2011, May). The old man and the sea. StudyMode.com. Retrieved from

http://www.studymode.com/essays/Ernest-Hemingway%27s-The-Old-Man_And_711547.html.

Baynes, C. (n.d.). Discussions with Jung. Retrieved from

http://dreams.00.gs/Red_Book,_0.B.htm

Bregman, M. (2012, June 22). The fisher king: Healing the feminine and the masculine. Flesh of the bone: dream descent through past life trauma. Retrieved from

http://www.fleshoffthebone.com/1/post/2012/06/the-fisher-king-healing-the-feminine-and-the-masculine.html

Chalquist, C. (2007). A glossary of Jungian terms. Retrieved from

http://www.terrapsych.com/jungdefs.html

Circle, H. (1915-2012). Posted by Braaten, J. (2012, June 24). Retrieved from

http://sportsmansblog.com/tag/homer-circle/

Crowley, V. (1999). Jung a journey of transformation. Exploring his life and experiencing his ideas. Wheaton, IL: Quest Books

Deffinbauch, R. L. (2004). How to hook a fisherman. Luke 5:1-11. Luke: The gospel of the gentiles.

Retrieved from

https://bible.org/seriespage/how-hook-fisherman-luke-51-11

Eliade, M. (1971/2005). The myth of the eternal return. New Jersey, NJ: Princeton University Press

Estés, C. P. (1994). Women who run with the wolves. Contacting the power of the wild woman. London, UK: Rider & Co

Fontana, D. (2010). The new secret language of symbols. An illustrated key to unlocking their deep and hidden meanings. London, UK: Duncan Baird Publishers

Goldsmith, J. S. (1973/2011). Conscious union with God. Radford, VA: Wilder Publications

Grace, M. K. (2011, January 31). The two fishermen’s house. Story lovers world. Connecting people through stories. Retrieved from

http://www.story-lovers.com/listsfishermanstories.html

Hall, A. S. (2003). Important symbols in their Hebrew, Pagan & Christian forms. Lake Worth, FL: Ibis Press

Hall, J. A. (1983). Jungian dream interpretation. A handbook of theory and practice. Toronto, ON: Inner City Books

Heroes 2011 Edublogs (2010, June). Mandala symbolism. (Web Log). Retrieved from

http://heroes2011.edublogs.org/files/2010/06/Mandala-Symbolism.pdf

Hill, D. (1982). From Anansi to Zomo: Trickster tales in the classroom. The reading teacher. Vol. 48, No. 6. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/20201475

Howe, L. (n.d). Depth psychotherapy Jungian sandplay. (para. Cosmos sea creatures, no two are alike. Beautiful and varied expression of the opposites. Fish) Retrieved from

http://www.highlandshealthandhealing.com/Depth.htm

Levy, P. (1999, May / June). The tension of the opposites. New connexion. Pacific Northwest’s journal of conscious living. Retrieved from

http://newconnexion.net/articles/index.cfm/1999/05/tension.html

Jung, C. G. (1959/2008). The archetypes and the collective unconscious. New York, NY: Routledge

Jung, C. G. (1961/1995). Memories, dreams, reflections. Waukegan, IL: Fontana Press

Kalff, D. M. (2003). Sandplay a psychotherapeutic approach to the psyche. California, CA: Temenos Press

LitCharts Editors (2007). LitChart on The old man and the sea. Retrieved from

http://www.litcharts.com/lit/the-old-man-and-the-sea/symbols

MCMurray, M. L. (1995). Beyond heroics. Living our myths. Newburyport, MA: Red Wheel Weiser

O’Connell, M. ,Airey, R.,& Craze, R. (2007). Symbols, signs & dream interpretation. Identification and analysis of the visual vocabulary and secret language that shape our thoughts and dreams and dictate our reactions to the world. London, UK: Lorenz Books

Parker, V. (2011). 50 Scary fairy tales. Classic stories with a creepy twist. Essex, UK: Miles Kelly

Publishing Ltd

Phillips S. J. (Executive Producer). Bosustow. N. & Wismar, C. B. (Producer). Weis, S. (Director). Uploaded (2010, September 5). Bosustow Entertainment Production. Acton Films, Inc. The golden book video: The fisherman and his wife. [Video file]. Retrieved from:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5SOqJgbo1nc.

Samdashani, S. (2009). The Red Book, Liber Novus. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company

Shepherd, R.,&Shepherd, R. (2006). 1000 Symbols. What shapes mean in art & myth. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson

Steinhardt, L. F. (2013). On becoming a Jungian sandplay therapist. The healing spirit of sandplay in nature and in therapy. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Tresidder, J. (2006). Symbols and their meanings. The illustrated guide to more than a 1,000 symbols – their traditional and contemporary significance. London, UK: Friedman

Tsekhanovskiy, M. (Director). Uploaded (2011, December 20). Generalfilm.Ru. Channel Soyuzmult video: The fisherman and the goldfish. [Video file]. Retrieved from

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KG0RiHT74yk.

Turner, B. A. (2005). The handbook of sandplay therapy. California, CA: Temenos Press

Turner, B. A. (Ed.). (2013). The teachings of Dora Kalff: Sandplay. California, CA: Temenos Press.

Turner, B. A.,& Unnsteinsdótter, K. (2011). Sandplay and storytelling: The impact of imaginative thinking on children’s learning and development. California, CA: Temenos Press

Comments are closed